This piece is from “Air Mail’s” September 9 issue used here with permission and my thanks.

I was surprised recently to encounter full and favorable reviews in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal for a new book called The Maverick: George Weidenfeld and the Golden Age of Publishing, a biography by Thomas Harding. It is based on complete access to the archives of Weidenfeld and Nicolson, the London-based publisher Weidenfeld founded (with the illustrious Nigel Nicolson) only a few years after he arrived, in his 20s, a Jewish refugee from Nazi-held Austria.

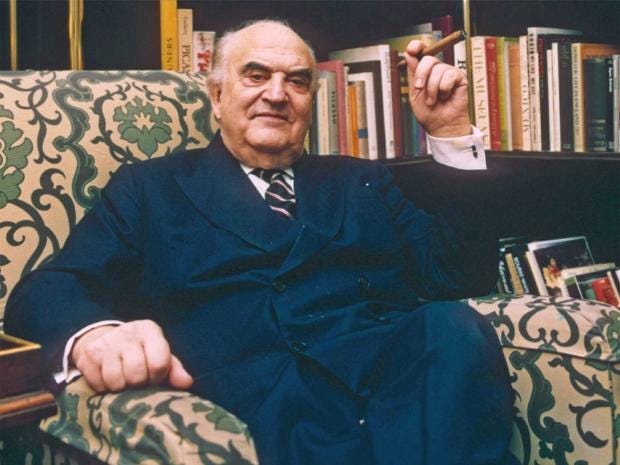

Really, I wondered, how many Americans are curious enough about this British publisher—he was Baron Weidenfeld of Chelsea, a member of the House of Lords, when he died at age 96, in 2016—to pay $29.95 for the hardcover released by Pegasus, a respected, small independent publisher in New York?

But because I, too, have been a book publisher (and could buy the e-book version for $21.19), and knew Weidenfeld a bit professionally and a bit socially, which just about anyone he met (especially young women) could claim, I read it, to be honest, overnight.

This is an entertaining read for those who enjoy literary gossip in which the list of dropped names is dazzling. There are asides, such as the footnote in which Weidenfeld was asked by the Irish writer Cornelius Ryan how he—“I mean let’s be frank, boyo, you’re fat, you’re bald”—had so many beautiful wives and girlfriends. “My dear Connie,” Weidenfeld is said to have replied, “it’s very simple. You see in certain circles, I am known … as the Nijinsky of cunnilingus.”

But Weidenfeld was also a publisher of legitimate distinction. Two of his earliest authors were Henry Kissinger and Isaiah Berlin. He defied convention to publish Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, and was the publisher of choice for statesmen the world over, historians, and journalists. At one point, he sold me, at Random House, the autobiography of Rupert Murdoch, which never actually got written. Money had to be returned.

Weidenfeld was a crafty operator in business. Whenever money was tight, he managed to find a benefactor. He and Ann Getty had a publishing company in New York that she underwrote and, she said, cost her millions.

As Lord Weidenfeld, he was a certified grandee. His home soirées were famous, numerous, and lubricious. I attended a couple when I lived in London. And yet my lingering image of him was at the Frankfurt Book Fair, where publishers gather to buy and sell rights. I glimpsed him in one small booth deep in conversation. With a fur pelt over his shoulder, he would be recognizable in a trading bazaar from another era.

The Times review of the book begins with a litany of reasons why book publishing has become boring. I wouldn’t go that far, while still agreeing that there is no one quite like Weidenfeld in the trade these days here or, I suspect, in Britain as well.

*****************************************

Next Week on Substack: When Print Was (Still) King: The Legacy Generation Passes On.