Five O’Clock Follies

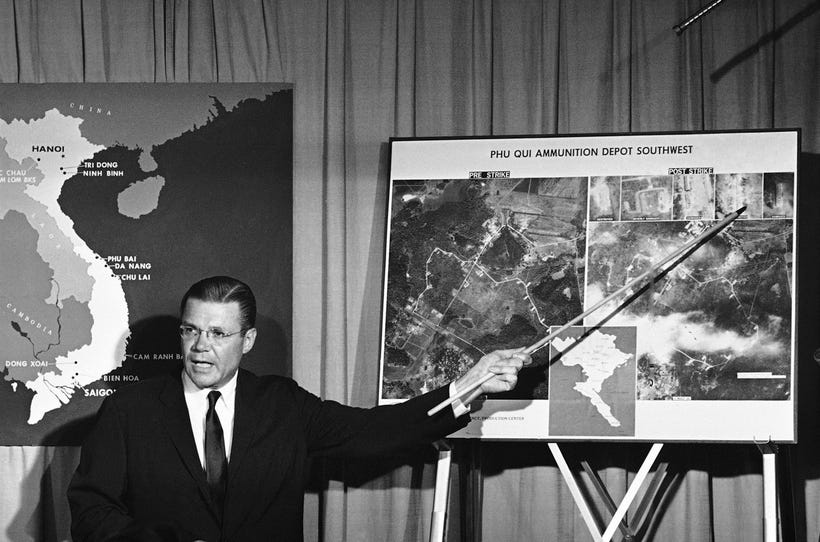

Lyndon Johnson and Robert McNamara knew the war in Vietnam could not be won—and waged it anyway

BY PETER OSNOS

Of all those considered responsible for the outcome of America’s Vietnam debacle, President Lyndon B. Johnson and Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara usually get the most blame.

It was they who turned a commitment of roughly 15,000 U.S. military advisers into a force of more than 500,000 combatants that proved unable to hold off the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong, leaving behind a unified nation aligned with the global Communist bloc.

As a correspondent in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos for The Washington Post between 1970 and 1973, and as the editor and publisher of major memoirs and histories on the subject, I have been immersed in the events of that era for a half-century.

This experience is what is contained in LBJ and McNamara: The Vietnam Partnership Destined to Fail, a serial that is running over 18 weekly installments on Peter Osnos PLATFORM, my newsletter on Substack. This amounts to a book delivered in a digital-word format for storytelling, the way podcasts do with audio.

Among the works I edited, the most significant was Robert McNamara’s memoir, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam, which, when published in 1995, renewed the sense that he, Lyndon Johnson, and their administration waged a war that Americans came to believe was an immoral display of superpower hubris.

In the memoir, the former secretary of defense acknowledged as much. “We were wrong, terribly wrong,” McNamara wrote. “We owe it to future generations to explain why.… We made an error not of values and intentions but of judgment and capabilities,” a formulation he devised as we concluded two years of extensive work together on the narrative.

Even so, McNamara’s words fell short of an outright apology, and thus there was never a chance that he would be forgiven for what happened. But the book and, later, Errol Morris’s Oscar-winning documentary, The Fog of War, based on his filmed interviews with McNamara, established an account of the collective mistakes and misleading statements of progress that made, and continue to make, Americans so skeptical of what the U.S. government says and does in shaping foreign policy.

There were hundreds of pages of transcripts from my extensive editorial sessions in McNamara’s Washington office, where I was accompanied by my editorial colleague Geoff Shandler and McNamara’s historian collaborator, Brian VanDeMark. When I reviewed these transcripts and listened to the tapes from which they were created, I realized that they were illuminating beyond what appeared in the memoir.

“We were wrong, terribly wrong,” McNamara wrote. “We owe it to future generations to explain why.”

To help others understand that process, I have posted a two-hour edited version of the audio at platformbooksllc.net, in which the four of us, at times laboriously, find exactly the best possible description of events—including some details that were considered too personal for the book, regarding individuals who have since died.

I was also the editor of the memoirs of Clark Clifford, who was a formidable unofficial adviser to Johnson and McNamara’s successor at the Pentagon, and the memoirs of Anatoly Dobrynin, the Soviet ambassador in Washington, who provided the Kremlin’s view of the war.

Lady Bird Johnson’s White House diaries were especially striking about Lyndon Johnson’s growing awareness that he was in a war that could not be won in any conventional sense—and his resulting despair. Similarly revealing was the unfinished memoir of National-Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, who left the administration in 1966 and was never vilified the way L.B.J. and McNamara would be.

Most important as a resource were Lyndon Johnson’s tapes—his copious recordings of himself in conversation, including with McNamara. Johnson’s tapes reflect how his surpassing ambitions and his legacy in domestic matters were undermined by Vietnam.

I also benefited from Robert Caro’s four-volume biography of Johnson, the fifth volume of which (currently in progress) will deal more deeply with Vietnam.

These resources, and with the work and support of VanDeMark, a professor at the U.S. Naval Academy, and Robert Brigham, a distinguished Vietnam historian at Vassar College, enabled me to present a portrait of L.B.J. and McNamara that shows—conclusively, because so much of it is in their own words—that from the day Johnson took over from the assassinated President John F. Kennedy, on November 22, 1963, until McNamara’s last day as secretary of defense, on February 29, 1968 (when he became so overcome with emotion at a White House ceremony that he could not speak), both men were aware that they faced a challenge in Vietnam that they could not meet.

But they went ahead, accepting the reassurances they received from generals, intelligence operatives, and diplomats that headway was being made—even when those pronouncements conflicted with the facts in the war zone itself.

The reality is that a great power cannot prevail in a conflict where the strategies are flawed. McNamara hoped that the lessons of In Retrospect might guide future administrations. All this happened in the 1960s, decades before the United States followed many of the same trajectories in its 21st-century wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

LBJ and McNamara: The Vietnam Partnership Destined to Fail is available to read in chapters on the Platform Books Web site starting this mont

The US lost in Vietnam because they had forgotten their own history. During the US war of independence in the late 18th century the American independence movement was up against the British Army, which at that time was one of the largest and best organized and equipped European forces. It should have been a walkover for the British, but as we know the US ultimately prevailed. In retrospect the US prevailed because to them it was an existential fight - they had their lands and their lives to lose, whereas if the British lost they would simply go back home. Forward to the Vietnam war, the Vietnamese were fighting for their own lands and lives, but the Americans, and particularly the troops at the sharp end, had no particular skin in the game and mostly didn't want to be there.

As Mark Twain said, it's not the size of the dog in the fight that matters, it's the size of the fight in the dog.