The United Kingdom has been through a Brexit upheaval and the Boris Johnson era. The country is now governed by Sir Keir Starmer’s center-left Labour Party. The Conservatives are led by Olukemi OIufunto Adegoke Badenoch. The recently crowned king and queen are in their seventies, their adultery in the past forgiven if not forgotten.

The United States has a president-elect, carrying thirty-four felony convictions and enormous fines for fraud and sexual assault and approaching eighty with a radical agenda based almost entirely on his personal preferences. He vows revenge on his opposition. So continues the decade-long Donald Trump political phenomenon.

**********************************

British publications usually feature a diary of items by an editor or columnist intended to frame matters in a personal way. In that spirit, here are notes from a family visit to London last week:

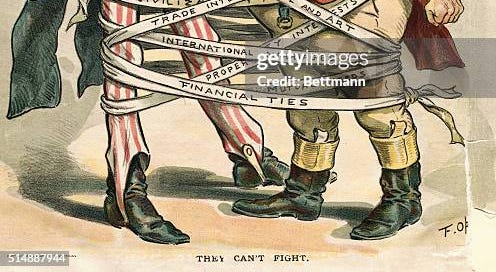

Just short of 250 years since the two countries did fierce battle to separate, the US-UK entente is as strong as ever. The “special relationship” in politics — epitomized by Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill or Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher — will be tested given what can be expected from the incoming Trump crowd. Think of defense collaboration with Pete Hegseth at the Pentagon and security secrets shared with Tulsi Gabbard as director of national intelligence. (If the Senate enables them to make it to confirmation).

But in many social and cultural ways, the countries are strikingly aligned. There is an economically challenged working class, a stressed middle class, and in the British parliament is Nigel Farage, a mini-me of Trump populism, who leads a Reform party that has the support, according to polls, of 20 percent of the British public. His rhetoric is meant to increase grievances about the present and unease about the future.

The popular culture and media overlap is expanding. Movies, books, and music are, as always, widely shared. CNN, The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post have British bosses. The New York Times has 100 people based in London and New Yorkers complain that the hometown is getting short shrift in coverage. In sports, American boys and girls starting at school age are playing soccer and their parents are watching much more of the professionals than in the past. And on our Thanksgiving day, there were three NFL games being streamed at pubs, I was told.

The bond between the West End and Broadway is exceptionally close. A Guys and Dolls revival is a current hit. Coming to New York next year is Operation Mincemeat, a musical based on the true story of how the British used a corpse carrying phony documents to fool the Nazis about where their troops would land in southern Europe. It has received the most five-star reviews ever recorded for a musical.

Buy tickets as soon as they are available.

**********************

Two books I finished before our trip define our ingrained two-nation entente, although more in the traditional ways than today’s version. Both books’ protagonists are British, and they challenged convention in their lives. Anglophile Americans especially admire singular and dashing style (think James Bond, Mick Jagger, Princess Diana, Victoria and David Beckham, and the “Iron Lady,” Thatcher); these two, in their time, certainly had that.

Kingmaker: Pamela Harriman’s Astonishing Life of Power, Seduction, and Intrigue by Sonia Purnell (published by Viking) is the biography of Pamela Digby Churchill Hayward Harriman, an epic saga of how she straddled the Atlantic — to use a deliberately suggestive term — using charm, sex, and ambition to arrive in her later years at a position of genuine influence in American politics. What a story!

Over the years I encountered her in several ways that enabled me to understand at a distance how she pulled off her trajectory. In the mid-1970s, when my wife and I were living in Moscow for the Washington Post, we received an unexpected call from an aide to say that Governor Averell Harriman and Mrs. Harriman were in the Soviet capital and would like to have dinner with us.

In those years, restaurants were not really an option. So we invited the couple to our tidy little apartment in a foreigners compound. We took down a silver tureen wedding present, filled it with black-market-purchased caviar, added brown bread and vodka, and served a meal that our guests seemed to appreciate.

In the late 1980s, Random House acquired what were to be Pamela Harriman’s memoirs, for what I recall was an advance of two million dollars. I was designated to be the editor. I hadn’t yet really engaged in the process when I learned that she had decided to cancel the deal, even after sitting with her prospective ghostwriter for about forty hours of interviews.

Apparently, Pamela had concluded that the details of her life were just not ready to be revealed in a book. The writer, Christopher Ogden, took the position that as the interviewer he could hold on to the material. And, incredibly, her lawyers agreed. He then wrote a salacious book called Life of the Party that was devastating and a bestseller.

Somehow Pamela regrouped. Living in Georgetown, she had already become a leading figure as a major influencer and fundraiser in Democratic politics. She was instrumental in what became the presidency of her friend Bill Clinton, who appointed her to be the U.S. ambassador to France.

I last saw her there in a long receiving line at an embassy July 4th party. She greeted me warmly as a friend, which I really was not, but I did get the aura of charm I was doubtless supposed to. She died in February 1997 of a cerebral hemorrhage, in a hotel swimming pool, at the age of seventy-six.

The second book is Believe Nothing Until It Is Officially Denied: Claud Cockburn and the Invention of Guerrilla Journalism by his son Patrick Cockburn (published by Verso). Claud Cockburn is not well known in the United States, although his sons, Alexander, Andrew, and Patrick, have had notable journalism careers here and in Britain.

What makes Claud Cockburn so fascinating is that in writing style and impact he was the forerunner of what has become the American approach to journalism, combining ironic wit, snark, and reporting. Cockburn’s newsletter in the 1930s, The Week, is a direct antecedent of today’s popular commentators on late-night television and internet destinations like Substack. Cockburn was a respected correspondent in the United States for the Times of London, but he was also a card-carrying member of the British Communist Party, an affiliation that was not then disqualifying for acceptance. Today’s far right in the U.S. contends that journalists are still communists although the party has disappeared.

***************************

So, a once great British Empire is gone, and while the United States increasingly finds its superpower status challenged, it remains vastly more powerful than Britain. For all the imbalance, it is still a “special relationship.” In both countries populations are much more multicultural than they used to be — immigration is a major and vexed issue. The large segment of the population who feel they are being left behind are damn angry about that. The United States was founded on the principle of defying rulers in imperial Britain. The 2024 election of Donald Trump and his political cohort is in many ways a rejection of our country’s more recent political leadership.

An observation often attributed to Churchill but more reliably credited to George Bernard Shaw is that “Britain and America are two countries separated by a common language.” Actually, the record shows that language is only one part of a much more intricate relationship.

Next week, Part Two: Parsing Britain’s Changed Political Scene

Tks

becomes.