Bombay Then; Mumbai Now

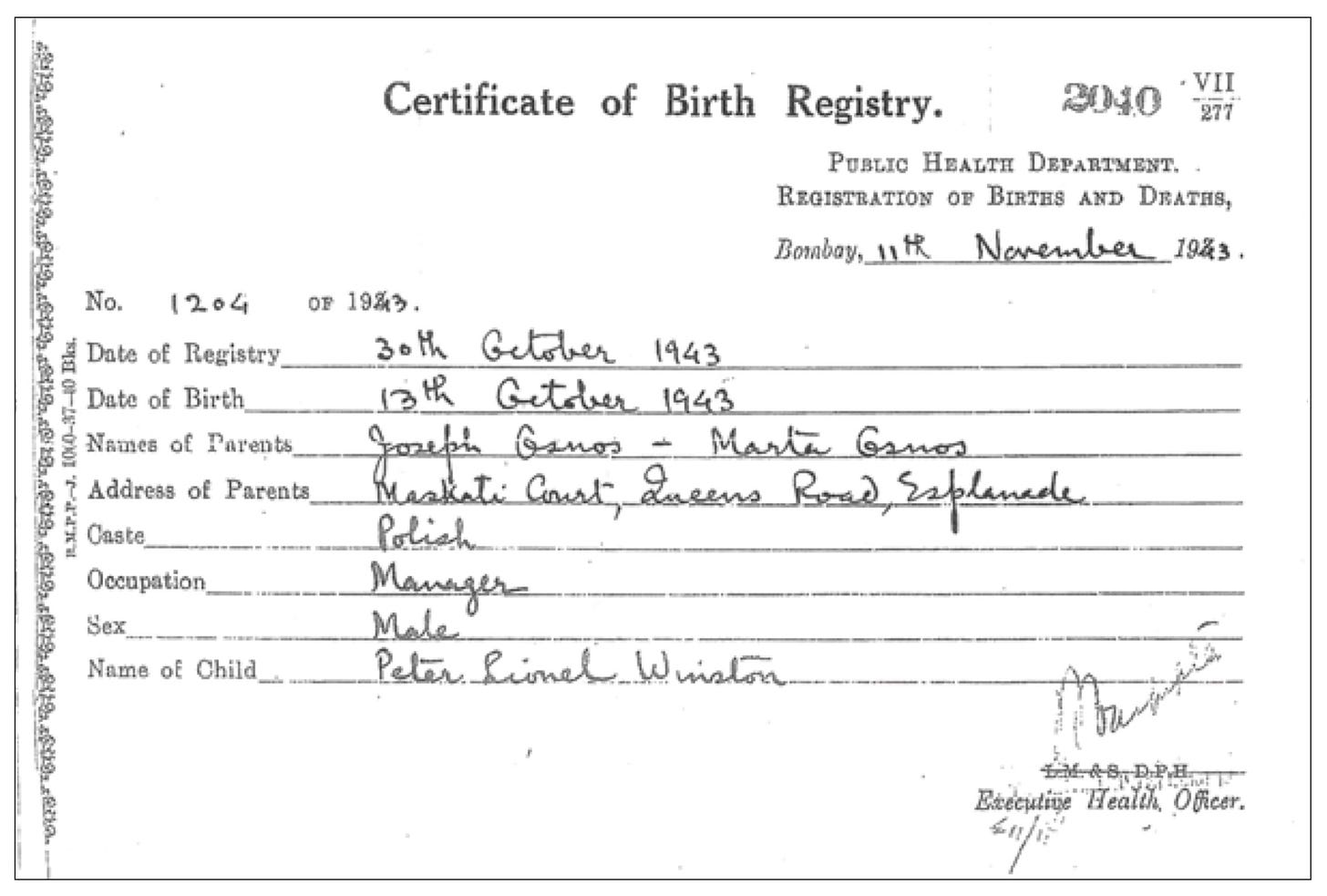

Over the holiday period, my wife, Susan, my teenage grandsons, Benjamin and Peter Sanford, and I traveled to Mumbai (aka Bombay). This was not my first stay in that South Indian megalopolis. I was born there on Oct. 13, 1943. My Certificate of Birth Registry says: Caste: Polish.

In December of that year, exactly 76 years ago, I accompanied my parents, Josef and Marta Osnos, both about 40, and my brother Robert, 12, on a 44 day journey across the Pacific on the troop ship, S.S. Hermitage, which was transporting Italian POWs to Sydney and then returning American GIs to San Pedro, California. There was also a small group of civilian passengers. I was in a basket.

The purpose of our trip was to learn about my family’s life in wartime India, still very much in the British Empire. They arrived in Bombay in June 1940 after a harrowing journey that involved escaping from Poland as the Nazis advanced, and gaining, in succession, access to Romania, Turkey and Iraq where an Englishman named John Mish helped them secure a visa to Bombay. He later turned up there as a high official of the British Criminal Investigation Department (CID).

With the assistance of an organization called the Jewish Relief Association, Bombay and a consul from what must have been the remnant of Poland’s defeated government, they began new lives in a place they had never been in practically the only Western language they did not speak, English. By the time they boarded the troop ship bound for America, they left behind an apartment overlooking Bombay’s most illustrious cricket pitch, solid jobs, a staff of servants and an Anglican boarding school in a hill town about a day’s bus ride from Bombay.

My wife and I arranged the trip through Banyan Tours Pvt. Ltd., using my mother’s notes and some recovered letters, telegrams and documents to identify the sites of the most important places in their story.

Those years in Bombay, were theirs and not mine. Now my family and I can do better than imagine what it was like to be them.

What follows is a summary of what we discovered as we made our way through an itinerary designed over months of effort: We stayed in the Oberoi Trident, one of Bombay’s best hotels, forever marked as one of the 12 venues attacked on Nov. 26, 2008 by a group of young Pakistani Muslim terrorists in a bloody rampage that is widely regarded as India’s 9/11. Our guide was Mogan Rodrigues, an East Indian who came from a long line of Portuguese who arrived in India in the 17th century when Bombay was a colony of Portugal. In a matter of days, he became a good friend, helping us track down landmarks, those that still exist and some that were merely fading signs. We even met 98-year-old Leonora Raymond (Auntie Nora to her neighbors), an Anglo-Indian woman who had lived in the same building as my parents did on Oliver Street, still a tree-lined oasis in the cacophony of the city center.

In the order of our encounters, here are my impressions:

St. Elizabeth’s Nursing Home

This is now St. Elizabeth’s Hospital on the same Malabar Hill site. The section of the hospital where I was born, a palatial colonial structure, is gone except for its foundation. The hospital is still “conducted” by St. Joseph’s Education and Medical Relief Society in a sturdy modern building. We spent an hour or so with Sister Angela, a resident nun, who expressed surprise and interest in my birth saga. My mother’s bill for confinement and other services was 150 rupees (at 15 rupees a day), which, Angela said, would indicate that my parents could afford quality care. This was evidence that my refugee mother and father had made their way into the comfortable upper-middle class life of Europeans in India, which disappeared after Independence in 1947.

What Sister Angela didn’t say then but became clear in an email she sent us later is that the hospital is facing a challenge. “We are getting swallowed by the Corporate hospitals,” she wrote, “and our bed occupancy is low. Do keep us in prayer. We have ideas like marketing etc.” An accompanying Power Point emphasized the hospital’s intention to serve more than the prosperous Malabar Hill location by an expansion in which the “rich help the poor.”

Where Josef and Marta worked

Josef had a background as an engineer and entrepreneur. Once in Bombay, he was soon hired by Art Flooring and Construction Co., Contractor to H.M. Army and Navy Shipbuilding Department. A reference letter written Dec. 24, 1943, the eve of his departure for the U.S. said: Mr. Osnos was a very valuable man to our company and his scrupulous honesty and good sense have endeared him to all our clients as well as the staff.” A note at the bottom said that the firm had been employed “extensively in defence works and Mr. Osnos has been of great assistance to us.” I can’t read the signature, but it is underlined Proprietor.

Marta was a scientist, short a PhD perhaps because she was a Jewish woman in Poland after World War 1. She went to work at Raptakos and Brett, a pharmaceutical company. The Polish consul had told her not to bother with work, she wrote in her notes because “I would be supervising my cook.” A fixture of family lore is that she later worked as a censor for the British, reading the mail from occupied Poland and France. We always thought that reading those letters must have been one of her favorite ever pastimes but we have no evidence of that. We did know that her colleague at the censors office, another Pole, went on to become the Professor of Sanskrit at the Sorbonne.

Both Raptakos and Art Flooring are gone today, but we did find the signage at their former locations that indicated that the companies were once there. On the whole, manufacturing has been moved out of the city to reduce pollution. There is a long way to go, acceptable AQI levels are measured at 50. While we were there, the daily count was over 185.

Once again, as Europeans in a colonial era, my parents went from haggard refugees to the professional class with astonishing speed.

Where They Lived

On arrival, my parents lived jointly with other families in a place so dubious that, my mother wrote, an Australian soldier stumbled in thinking it was a bordello. Soon they were in an apartment on Oliver Street, four rooms, with a kitchen, bathroom and a veranda. There were two other couples. “One couple was quite famous, Lena Zelichowska, a very popular actress and Stefan Norblin, a painter.” Several of Norblin’s works made it to my parents’ apartments in New York. The other couple was Wanda and Crestaw Knoff, “she very beautiful and he an engineer…We had one servant and the evening meal we had sent from the little restaurant across the street.”

I don’t recall ever hearing about the Knoffs. But “Auntie Nora” did remember them as exceptionally nice. A woman we met walking her dog on the street told us about Nora and assured us that the she was in complete control of her wits, despite being almost 99. And she was. She said she had already lived twenty years longer than she expected to and saw no reason not to go on. She talked vividly about clients in her beauty salon. When she spoke, we recognized an accent that would have been acceptable in an elegant London dinner party. We couldn’t tell whether she had ever married, but she must have had suitors. She said she was devoted to the British Royals and was proud to be known as the Queen of Oliver Street.

She had beds for servants, but we only saw one. The apartment badly needed painting and was dusty. Nora did not seem phased. A highlight came when she told us that her laptop with the Scrabble app no longer worked. She did still have the board game, however. Our grandsons installed a Scrabble app on her cell phone, which she said she doesn’t use. On a table was a book about taking charge of your health.

Once Josef and Marta got their jobs, they moved to the Maskati Court flat which had been renovated for them. A veranda overlooked cricket players on the Maidan. “We had two bedrooms, two bathrooms, a large living room, a dining nook and kitchen,” she wrote, “there were separate servants’ quarters.” Apparently, they rented out one of the bedrooms, so when my brother was home from school on vacation, he slept on a couch in the living room.

We didn’t get into the building, but it seemed in good shape. The cricketeers at play were all dressed in white and all, of course, were Indians. Cricket remains a favored Indian sport.

The Ring

My father always wore a gold ring with an intricate design on the face which he never identified. After he died, the ring disappeared, and we assumed someone had removed it in the burial process. After 20 years it turned up in a random family drawer. I now wear it. In an atelier in a heritage home owned by a designer and civic activist named James Ferreira, I showed it to a young woman manager (whose name I regrettably do not have) as we stood next to a display of jewelry. Immediately she said, that is a frog on a lotus leaf. A quick Google check came up with many illustrations of frogs on lotus leaves. According to the web, the frog is a “a symbol of renewal” in India. And lotus leaves are said to signify beauty and purity of spirit. We chose to believe that Josef who wore no other jewelry had the ring made when he and Marta concluded that they had finally reached safe haven.

Saint Peter’s School

Once my parents had jobs and Robert had studied some English, he was enrolled in an Anglican boarding school called The European Boy’s School in Panchgani. Panchgani, a hill town about a days’ bus ride from Bombay, is what the British called a hill station. Cooler than the cities, it is a popular destination for rest and recreation and a good place, it seems, for boarding schools. To get there in 2019, you take a train to Pune (first class is the equivalent of the quiet car on Amtrak’s Northeast Regional) and then drive about three hours on winding but well-paved roads to Panchgani. We stayed in a “resort” hotel (featuring Western plumbing and a pool). It happened to be New Year’s Eve, so we were on hand for the celebration of mostly local families with a buffet, balloons, prizes for children, music, dancing and New Year’s resolutions.

The next morning, we went to what is now called St. Peter’s Boys School, located across 60 acres on a picturesque cliff. It was founded in 1904 and most of the buildings date as far back as the 1920s, but have since been refurbished. They still carried English names. (Ashlin, Cornwell, Drury and Rowan). The school motto is “Ut Prosim,” which means “that I may serve.” The maroon and gold school jacket and crest marked by a phoenix appears to be unchanged from the one my brother wore in a picture taken with my mother. The school calls itself Anglican, but says it welcomes boys of all faiths. My sense talking to the headmaster and one of the teachers (the boys were away on vacation) is that most of the students are Christians. India has about 30 million Christians, the third largest religious group after Hindus and Muslims. The headmaster, Wilfred Noronha is himself a Catholic. He said he survived a terrorist bombing of the Mumbai subway in 2006 and has dedicated his life to piety and education. There are 193 boarders and 88 day-students. The tuition and fees are the rupee equivalent of about $5000. There are no scholarships.

In Robert’s time, most if not all the students were European. Unfortunately, most of the records of the early 1940s were destroyed in a fire in 2008. We did see photographs from the 1930s and plaques with the names of outstanding boys in 1941–1943.

St. Peter’s most famous alumnus is Freddie Mercury, lead singer of Queen and the subject of the hit movie, Bohemian Rhapsody. His picture is prominently displayed in a main building. Most of the boys, Noronha said, come from families determined to get the best possible educations for their sons. (There is a girl’s boarding school in Panchgani also.) And some of the boys are there, he conceded because the families are exasperated with their teenage behavior. The most “elite” of Indian students still favor schools in the United States and U.K. He proudly noted that St. Peter’s has been rated one of India’s top ten private schools.

Robert never spoke much about his time in the school. But when he was in his 60s, we found a few letters he had written to our parents. He wrote in childish Polish and emphasized his loneliness. He had been advised by Marta not to tell anyone he was Jewish, so he participated in all the Christian observances. His principle grievance was the need to take castor oil for “digestive health.” From other conversations it turns out that for that generation castor oil was considered a price of civilization.

Perhaps the best way to characterize the impact of the school on Robert was in the reports written about him when he graduated from Columbia University’s medical school in 1956. Osnos, they wrote, was “a serious young man of British extraction.” In the Ivy League of mid-century America that apparently sounded better than Polish-Jewish refugee.

Robert was naturalized along with my parents and me in 1949. He had a long and successful career in psychiatry. He and his wife, Naomi, had two daughters and two grandsons.

The exact motivation to send Robert to boarding school at the age of ten was never discussed with our parents. Robert is now 88 and when I asked him what he thought was the reason, he said “it must have been convenient.”

What we discovered about the Osnos family in Bombay was an extraordinary combination of resourcefulness, determination, talents and luck. In April 1943 they succeeded in getting visas to the U.S. which at that time were very hard to obtain. I was born six months later. There are 12 years between my brother and me. Our parents had waited to be sure they were on stable ground before having a second child. They gave me a middle name of Winston, a tribute, I suspect, to their three wartime years in Churchill’s India. My father believed that after independence, which he was sure was coming, Europeans would be less welcome in India. So, they left that life behind and sailed across the Pacific at the height of the war and started again in New York.

Mumbai, Now: The Modi Factor

Narendra Modi won a decisive victory for his nationalist party last year and now is in his second term as prime minister. I think it is fair to say that he is the most formidable Indian leader since Indira Gandhi, the daughter of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister after independence. She served from 1966 to 1977, and in 1975 declared a state of emergency for a variety of political reasons, enabling crackdowns on civil liberties. Nonetheless, she was re-elected in 1980 and then assassinated in 1984 by her bodyguards and Sikh nationalists in 1984.

Probably the best recent expert reporting by an American of Modi’s increasingly authoritarian rule, which, in particular, is considered discriminatory to the country’s 200 million Muslims, is by Dexter Filkins of the New Yorker in a piece called “Blood and Soil in Nerendra Modi’s India.” (link). I found a shorthand description of this period in a letter to the magazine from Harish Sethu of Ardmore, Pa. who wrote: “Modi like Donald Trump has shown that latent bigotry is a deep resource, more easily mined and exploited by a demagogue than polite society ever allowed itself to believe.”

Democracies are always at risk; all societies have some form of prejudice, racism, inequality and potential for upheaval. This is, from all, accounts, a fraught moment in Indian politics along with a relative slowdown in its expanding economy. I’m going to wager that the successes of India’s modern history and the buoyancy of its 1.5 billion people, the majority of whose lives are an upswing, will forestall a debacle in social order — like the one engendered when the British left in 1947 partitioning the country into Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan with the death and displacement of millions of people.

The Taj

The terrorist attacks in Mumbai on November 26, 2008 were horrific, killing and wounding hundreds and lasting three days before all but one of the terrorists was killed by Indian police and special forces. He was later hanged. Of all the places attacked, the focus was on the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, an iconic vestige of the colonial period adjoining the arch known as the Gateway to India, a symbolic pillar of the state. As with 9/11 in New York, 11/26 as it is called, seems to be a defining moment for the country. Life before and after is measured by the Taj events, at least in Mumbai. Security in the city is pervasive (although I have no idea how effective it is except that there has been no repeat of the attacks). One indication of Mumbai today is that to get into the Starbucks near the Taj, customers go through a metal detector and have their bags checked.

The Mobile Phone

It is hardly revelatory that the cell or mobile phone increasingly just known as the “device” has had a profound effect on life globally, including India. They are quite literally everywhere including among the early morning sellers at the fish, vegetable and flower markets, whose work is otherwise unchanged in a century at least. A mobile phone, our guide Mogan said, makes even the very poor feel part of the modern world, certainly as much as running water and an electric light. There are 800,000 million of them now in use, especially remarkable considering that smart phones first appeared less than 15 years ago. Because of the vast customer base, the phones and service seem affordable. I don’t think it is an exaggeration to say that the cellular phone is one of the greatest advances in civilization since the wheel.

And Finally

Some numbers that take India to 2030 from the Sunday Times of India, December 29, 2019 drawn, the newspaper said, from “thousands of data sets to project samples of life ten years from now.”

-Every Indian could have access to the Internet by 2026

-On an average, Indians will at least double their nominal income

-Nine out of ten Indians will be literate.

-They will live twice as long as their great grandparents did.

-Nearly half a million will go to the U.S. for studies every year.

All I can say about that last prediction, is that the United States would do well to encourage them to come.