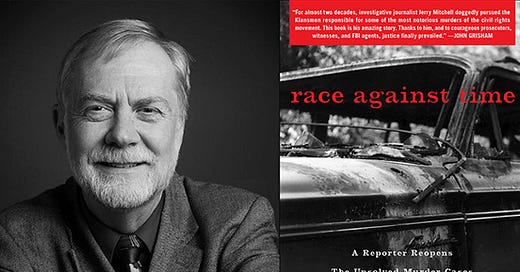

Jerry Mitchell has been an investigative reporter in Mississippi for decades. Over those years, he has been responsible for many of the biggest stories to have come out of the state. Here’s a glimpse from Mitchell’s illustrious career biography:

His work helped put four Klansmen behind bars: Byron De La Beckwith for the 1963 assassination of NAACP leader Medgar Evers in 1963; Imperial Wizard Sam Bowers, for ordering the fatal firebombing of NAACP leader Vernon Dahmer in 1966; Bobby Cherry, for the 1963 bombing of a Birmingham church that killed four girls; and Edgar Ray Killen, for helping organize the 1964 killings of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner.

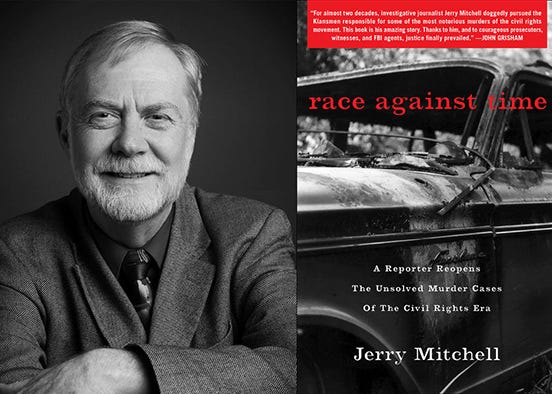

Mitchell wrote a well-received book, Race Against Time, about these cases and the courageous pursuit of justice by the victims’ families. He has received more than thirty national journalism prizes and a $500,000 MacArthur “genius” grant.

I asked him how he’s been compensated by his employers for his exemplary efforts. “Sure,” he replied, “I could have gone to New York and made a lot more money. But I feel we can have far more impact here in Mississippi, where the need is far greater, and I feel far happier because I’m living for others and not myself.”

Jerry Mitchell is by any measure a great journalist. He is now sixty-six and is an investigative reporter for Mississippi Today, the nonprofit news organization founded in 2016 that has become unquestionably the most important source of reporting in and about the state.

Mitchell is known and respected in Mississippi, but he’s certainly not famous or a celebrity, as so many of his counterparts in the media big time aspire to be. And that is by choice. When the New York Times approached him about a job, he said he only wanted to cover Mississippi, so nothing came of the offer.

*****************************

Jerry Mitchell was born in Springfield, Missouri, where his mother and father just happened to be at the time. “Mom came for a baby shower and had me instead,” is Mitchell’s explanation. He was raised in Texarkana, Texas. His father became a Navy jet pilot (his dream job), and he went to his parents’ alma mater, Harding University in Searcy, Arkansas.

While still a student he started reporting for the Texarkana Gazette and moved with his editor to the Jackson Clarion-Ledger in 1986. That paper, long a racist mouthpiece for the state’s white citizenry, had turned around enough to win the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 1983 after having been sold to the Gannett national chain the previous year. Mitchell said he was proud to be taken on there.

As a courthouse reporter, he was inspired by the 1988 film Mississippi Burning based on the unsolved murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner to start investigating these cases, which Mississippi justice either would not or could not resolve.

Mitchell says there was nothing in his background that had particularly guided him toward civil rights and the African American experience. But his instincts for what he knew to be terrific stories motivated him. I asked him what makes an investigative reporter.

“You are never satisfied until you uncover the facts that officials don’t want you to know,” he said. His commitment to civil rights and justice reporting was not political activism. It was a determination to get at the truth of events — with details so thoroughly persuasive that, even against the odds, perpetrators will be identified and convicted.

Mitchell’s family lives in Texas, but Mississippi is his home; it is where the stream of stories that he does so well seems never ending. The success of Mississippi Today as a flourishing enterprise is one of the country’s best examples of the reinvention of local news with funding from philanthropy and paying members. Its news output is free and shared with the state’s newspapers, including the once formidable Clarion-Ledger, which like thousands of other advertising-dependent news organizations across the U.S. has seen its resources and stature diminish.

Today’s Mississippi is not the officially segregated and racist state it was in the 1960s, but the powers-that-be still need especially close monitoring. Former Governor Phil Bryant sued Mississippi Today after its reporter Anna Wolfe disclosed major welfare fraud, which won the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting. The next year, a group of young New York Times-supported reporters worked with Mitchell on a series exposing the notorious brutality and corruption of sheriffs around Mississippi. That work was a finalist for the 2024 Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting and for Harvard University’s Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting.

In fact, Mississippi Today’s partnership with leading national news organizations like ProPublica, the Marshall Project, and the Associated Press is an encouraging feature of the reinvention of local news underway elsewhere.

News organizations have always needed two parallel lanes to flourish — outstanding reporting on the communities, small and large, where they are located, and the financial resources to pay for the reporting, editing, and distribution to their readers.

It was in 2019, when the Jackson Clarion-Ledger was going through its third round of buyouts and layoffs, that Mitchell decided to leave and start the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, which he merged with Mississippi Today in 2023.

What enables nonprofit journalism to have enough impact in their areas to attract the financial support that is indispensable is the quality of its news, especially investigative reporting — which creates accountability for the actions of officials and public institutions.

When Jerry Mitchell thinks of getting things done, his focus on accountability is his strength. I am calling him a superstar, which I am sure is something he would never say about himself.

I'm checking out Race Against Time at the library after work today. Thank you for putting this on my radar!