Good Books. Any Way You Want Them. Now: A Publishing Story

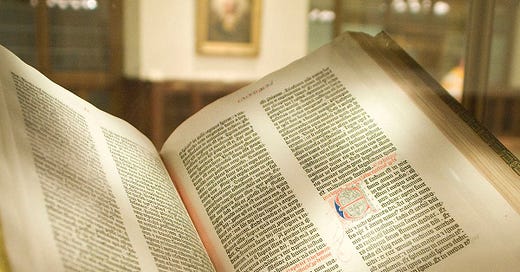

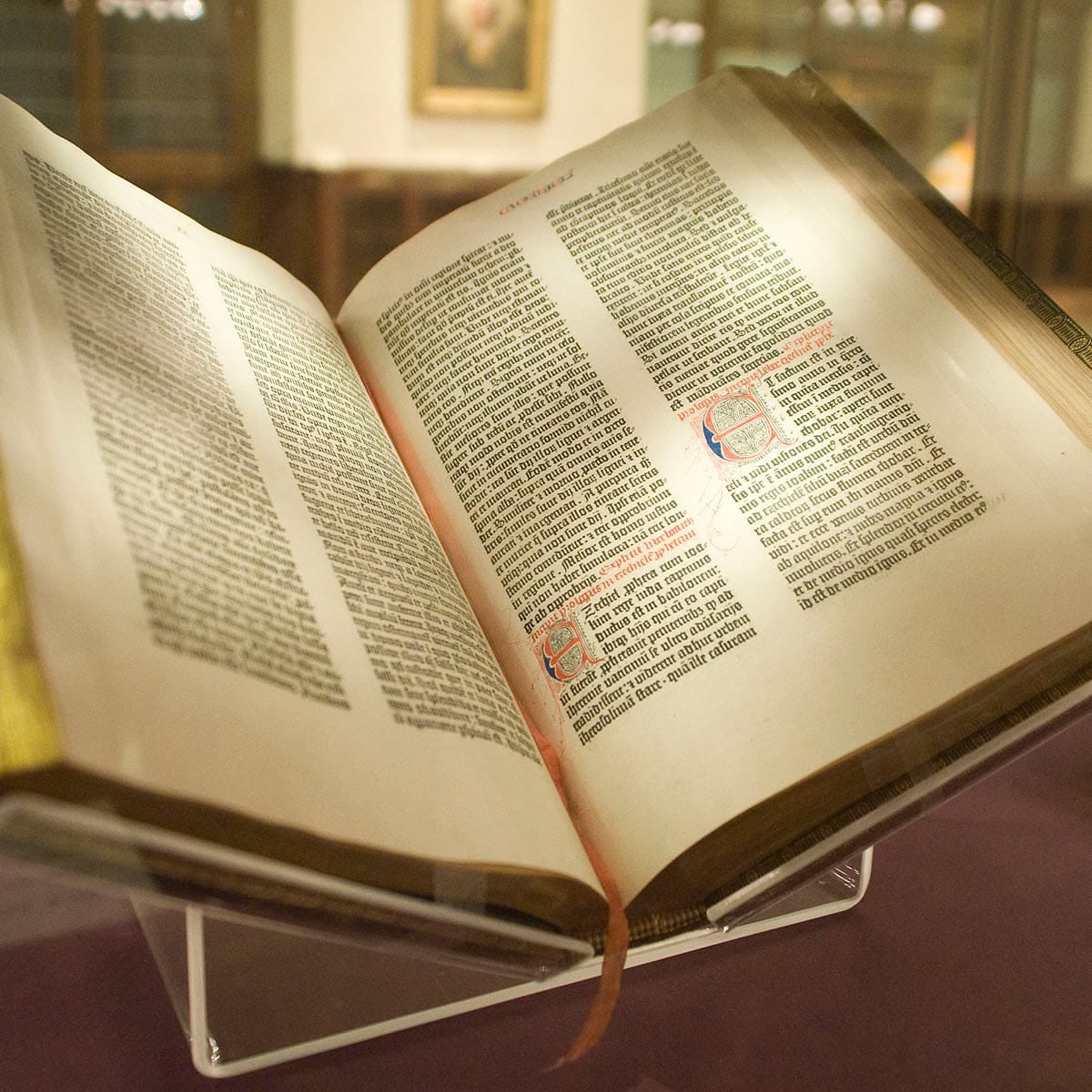

There is a venerable trope in the book world that the first major work published in movable type was the Gutenberg Bible in the 1450s. The second work, it is said, was called “Publishing is Dead.”

The decline or demise of reading and publishing is a perennial theme of commentary outside or, on occasion, inside the publishing orbit. But the reality is that down through the centuries books have repeatedly defied the odds, most recently in the predicted takeover of printed books by E-books and other digital innovations.

That is only the latest of the many developments in the 20th and 21st centuries that were thought to be the downfall of books including the commercialization of the Internet, the spread of soulless corporate entities, the decimation of knowledgeable local booksellers and libraries by chains and superstores and now the supremacy of a single on-line retailer, Amazon (whose founder and chairman, Jeff Bezos, also owns The Washington Post).

To some extent all these factors have been part of the story of books. But as I consider the time since I came to book publishing in the 1980s and, in particular, the last two decades, the insight to share is not how bad things are but how much has been proven to be stable or resilient.

Consider the Harry Potter phenomenon as one extraordinary example. J.K.Rowling’s series that began as a mother’s creative notes connected an entire generation, so far, around the globe to the excitement of great storytelling between covers and by extension to other platforms, from films to theme parks.

What is clear is that the time honored experience of reading books is to a great extent immutable. What is constantly changing is the way they are encountered: this is Content versus Distribution.

The occasion for these thoughts is the 20 year anniversary of PublicAffairs (one word cap A), the imprint which I founded. In 1997, a group of investors, including me, established a partnership. Our goal was to publish books that had immediacy, topical relevance and lasting value. The imprint was dedicated to three people who had been mentors of mine in a lengthy career: I.F. Stone, the radical journalist with an eponymous weekly; Benjamin C. Bradlee, the charismatic executive editor of The Washington Post, where I worked as a reporter and editor for 18 years; and Robert L. Bernstein, the long-time chairman of Random House, who combined a passion for human rights with enormous business savvy.

This combination of entrepreneurial energy and commitment were the values that PublicAffairs sought to maintain. So here we are 20 years on, still a rowboat in the great sea of media. I will leave to others to judge how we are meeting those objectives. In any case, we are continuing to try under the leadership of my successors as publisher, Susan Weinberg and Clive Priddle.

So what is happening with books? Beyond (most) dispute is the fact that fine literature is appearing in English and doubtless in languages less accessible to Americans with piles of, well, lesser, stuff also. Consider, for instance, the span between Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” and E.L. James’ “Fifty Shades of Grey,” bestsellers both. Has it not been ever thus? I am not really qualified to assess fiction: controversy is inherent in any judgement.

As for non-fiction, I believe that the quality, range and output of publication in all formats — hardcover, paperback, E-books and audio — is impressive. Every era has its strengths and its embarrassments. For every Robert Caro in biographical history, there are many cheesy celebrity quickies. It is notable that almost anyone who has momentary fame or a political role takes to books to shape their long-term reputations or as a payday.

In 1987, as a senior editor at Random House, I was tasked to handle Donald J. Trump’s “Art of the Deal.” In 1995, as publisher of Times Books at Random House, I was responsible for Barack Obama’s memoir “Dreams of My Father.” These books have improbably become emblematic of succeeding presidents. They are, in their way, destined to be classics for what they reveal about the men whose stories they told.

Whatever else is happening in journalism these days, the stream of investigative, narrative, historical, economic, sociologic, scientific books and enormously popular genres such as self-help and religion is vast. Overall sales of non-fiction have essentially kept pace with population growth. After all the annual statistics have been analyzed what they show is that readership is widespread, but hardly universal, pretty much where it has always been.

That brings us to the issue of distribution which has undergone huge changes over the years. In the 1980s, the most conspicuous booksellers, on the whole were known as “mall chains,” Walden and Dalton spread across the country featuring selections of the most popular books and categories. Barnes & Noble was mainly a college bookstore. Amazon was still a river in Brazil. And there were thousands of small “independents” which held community pride of place and were essentially unchanged from their predecessors of the past.

As a newcomer, I recognized that people tended to think of buying books, aside from current bestsellers, as a hurdle as in “I’ll see if I can get that book.” If it was not in stock, the book would have to be ordered, meaning that there usually was a wait and a second visit to the store.

In the 1990s, the fate of “mid-list” books — a dreadful term suggesting mediocrity — as distinct from those with bestseller ambition was in doubt. Imprints like Basic Books at HarperCollins, The Free Press at Simon & Schuster and Times Books were under financial pressure. As a reaction, the business model of PublicAffairs was conceived in the view that the constituency for what is called “serious non-fiction” was largely the same as NPR, PBS and C-SPAN, a fraction of the national population but an identifiable and durable one. Overhead and operating costs had to be forecast at a sustainable level. The mall stores were not likely to be our principal venue and many of the “indies” had limited stock.

In the next phase, based on the example of Borders in Ann Arbor and Tattered Cover in Denver, the concept of “superstores” took hold. These were large emporiums with tens of thousands of books and at Borders, the first steps toward computerized record keeping and ordering. These stores were so successful that Borders expanded nationally. A daring businessman named Leonard Riggio took Barnes & Noble from its New York base to a country-wide behemoth with huge impact on availability and pricing.

The indies were getting hammered by superstores. The mall stores and some smaller chains like Crown Books in Washington D.C. slipped and eventually disappeared. In the mid-1990s, Jeff Bezos conceived the notion of a virtually limitless on-line bookstore with a philosophy of “under-promising and over-delivering” on very tight profit margins. The Internet pricing was set far below that which sellers with brick-and-mortar overheads could match. We now know that Bezos had plans far beyond books to become the leading marketplace of everything.

Over the next decade, the Amazon impact on publishing was profound. When it unveiled the first Kindle e-reader in 2007, the era of digital books had arrived. Instead of searching for books, all that were available digitally could be had in under a minute. With the adoption of E-books and expanding inventory came the perception that E-books would eventually supplant printed books. Others rushed in to challenge the Kindle. Barnes & Noble in particular made a very significant and costly pitch into the arena. Meanwhile, Borders which despite its early computerization never really reckoned with E-books started to struggle financially and to the chagrin of book people everywhere went bankrupt and shut down.

But the undeniable disruption of books that was underway was handled more successfully by publishers than counterparts in, for example, newspapers and magazines where print advertising dropped at a shocking pace. Books, of course, had no advertising and therefore nothing to lose. What did happen, however, was a move toward consolidation among publishing companies. Simon & Schuster added Scribner. Random House and Penguin merged creating an international giant. The Perseus Books Group was a melding of imprints including Basic Books which was acquired from HarperCollins, where it was going to be closed. And our PublicAffairs partnership. The plan was to enable a diverse assortment of imprints with clear and separate editorial identities to benefit from the efficiency of central services. Perseus evolved into what the industry regarded as a “mini-major.”

The independents seemed to be in a swoon and generally gave little attention to E-book sales. Instead, the most enterprising owners made their stores into neighborhood destinations offering events, clubs,coffee bars and personal service as an incentive to make customers into fast friends. Today there are fewer indies than there were, say, 20 years ago. But those that have updated their approach to customers (We Deliver!) are bustling. Barnes & Noble took a heavy hit from its foray into E-Books and from a variety of management mishaps. It has been substantially weakened. Publishers recognizing that B&N is still a major source of sales began to regard the once feared chain as a valued asset, that would be greatly missed if it went under.

Meanwhile, Amazon has become the most powerful factor in the book business, certainly greater than any other, perhaps ever. It dominates digital books and has a very large share of the growing market for downloadable audio books. It also sells the largest percentage of print books and tussles regularly with publishers over terms of sale. A note to authors: Amazon orders its books in large measure based on the number of orders received before the books are even released. So the process of promotion starts almost as soon as the writing is completed.

After a surge in the early 2000s, the E-book spike has apparently peaked. They now have a share of overall sales, somewhere between 20 and 25 percent, although a bit higher in fiction. So printed books have prevailed as the format of choice in the competition for readers, at least so far. My motto for today’s publishing has become “Good books. Any way you want them. Now.”

What then is the proverbial bottom line for books? Overall, the traditional book has been, perhaps surprisingly, consistent in this time of fundamental change in technology and public habits. There are publishers large and small serving mass audiences and niches. Five conglomerates, with scores of imprints, including the Hachette Book Group which acquired the Perseus Books Group in 2016, are the industry giants. What the Perseus imprints, including PublicAffairs, can do is add to the audiences that they reach with meaningful but not necessarily mass-market appeal. In its way, this is a triumph of the underappreciated mid-list.

As founder of PublicAffairs, the fact is that publishers like us need to reach a balance between preserving our editorial mission and earning revenues sufficient to maintain the confidence of our proprietors. We are not Amazon, Apple, Google or Facebook, distribution empires that are stock-market high-fliers. They have been the lucrative pipes through which what is mainly other peoples’ content has to flow. Now they are moving into their own content also, which may make them a coming challenge for all those in the storytelling fields.

The long history of books is reassuring about the past and present and in a tumultuous period, successful publishers and booksellers have shown an essential ability to adapt to change. The need for that quality never ends.