Will American voters go to the polls next November to choose between former President Donald Trump and President Joe Biden?

As with so many others you and I know, I hope not. But unlike what pollsters contend is the majority of the populace, I don’t accept that this will happen. Why?

Instinct suggests that given who these men are and the times in which we live, something will almost certainly upend the forecast.

So, let’s assume that at some point in the next six months, beginning this month with the Iowa caucuses and ending in June, either Trump or Biden leaves the race, for any conceivable reason. Who then will be at the top of the tickets at election time and how will they get there?

I asked three of the country’s leading experts in the presidential selection process and politics generally for their views. They are Elaine Kamarck, the director of the Center for Effective Public Management at the Brookings Institution, Dan Balz of the Washington Post (who amazingly was already a sage forty years ago when we were colleagues on the national staff of the paper), and Larry Sabato, the Robert Kent Gooch Professor of Politics at the University of Virginia, where he is the director of the Center for Politics.

Substack helpfully enables links to their email responses to my questions, Kamarck, Balz and Sabato,

To summarize:

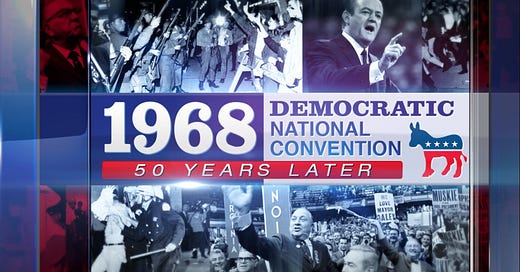

In the 1968 election cycle, President Lyndon Johnson withdrew from the race for the Democratic presidential nomination at the end of March. Over the following months, Senator Eugene McCarthy’s insurgent campaign lost momentum and Senator Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated after winning the California primary. The Democrats nominated Hubert Humphrey, LBJ’s vice president, who had not competed in a single primary that spring.

The chaotic 1968 convention in Chicago and the victory of Richard Nixon in November led the Democrats to establish the McGovern-Fraser Commission, for the purpose of reforming the delegate selection process away from the dominance of party bosses in “smoke filled rooms” to committed delegates chosen by voters in primaries. The new system went into effect in 1972.

The Republican Party also shifted its process, although less formally, by having primary voters, rather than party influencers, select delegates to the convention.

As a consequence, the national party conventions became essentially victory rallies for the candidate with a majority of delegates. The last real suspense was at the 1976 Republican convention, where the incumbent (but unelected) president, Gerald R. Ford, had to beat back a challenge from former Governor Ronald Reagan of California in an actual convention vote.

The conventions, despite the parties’ best efforts at providing drama and disputes, became so predictable that the national broadcast networks cut back to an hour of coverage each night, leaving the propaganda and bluster to cable, C-SPAN, and PBS.

The short answer to what would happen if Trump and/or Biden dropped out is there is no short answer. The likelihood is that the conventions, one way or another, would again become the places where the parties’ choices of president and vice president would ultimately be made.

Delegates from states where primaries had already been held before the dropouts would be technically committed, but in fact would be able to make whatever choices they wanted.

In other contests, state parties could and would adopt new rules. The names of announced candidates (or identifiable surrogates) would be on ballots for preferential voting. Delegates would arrive at the conventions presumably able to make up their minds.

In other words, this would be something of a free-for-all in which announced candidates would be scrambling for support among the delegates. Now that would be television worth watching.

(A caveat: since this situation would be, in its way, unprecedented it can be expected that shenanigans will ensue to gain the necessary margin, either at the conventions, through the courts, or in “smoke filled rooms.”)

Among the remaining questions:

Would Biden be obligated to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris as his successor? That would be a dry-eyed judgment call for the president. Harris would certainly expect that he would. And if Biden had actually left office before the convention or before the November voting, she would be the incumbent president.

I suppose if both Biden and Harris were to be out of office, the presidency would go to Speaker Mike Johnson. Good grief.

Which Republican would Trump endorse, if he were to bow out of the race?

The candidates running against him now are floundering in various stages of irrelevancy. Trump’s style might well be to pull a fast one, endorsing someone like former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, former Governor Mike Huckabee of Arkansas, or even the former Fox News personality Tucker Carlson. Do I have any insight on this? Absolutely not.

And what if Trump and/or Biden dropped out after the conventions? Presumably, the vice presidential running mate would take the top spot, but that’s not certain. The only similar (but not identical) situation occurred in 1972, after Senator George McGovern received the Democratic presidential nomination. When it became known two weeks later that McGovern’s running mate, Senator Thomas Eagleton, had undergone electroshock treatment for depression, it was considered disqualifying, and McGovern replaced him on the ticket with Sargent Shriver.

What definitely is the case: the majority of Americans by any meaningful measure consider a Trump-Biden election a terrible prospect for all the reasons the media are pounding us with every day. But wherever momentum is, the direction can change almost immediately based on the unforeseen.

On November 4, 1979, two events took place that were a surprise. In Tehran, Iranian protestors took over the U.S. embassy, creating a hostage crisis that only ended on the day Ronald Reagan replaced Jimmy Carter as president. And that evening Senator Ted Kennedy, the heir to the family political dynasty and a challenger to President Carter for the 1980 Democratic presidential nomination, was interviewed by Roger Mudd on CBS. When asked why he wanted to be president, Kennedy fumbled the question so badly that his candidacy never recovered.

I was the Washington Post’s national editor at the time, and with our staff I spent 1980 chasing the consequences of circumstances we hadn’t known were coming.

Positing political uncertainty and exciting conventions in 2024 sounds like fun. But the reality is that who is president of the United States on Inauguration Day 2025 could not be more serious.