In Print, Ebook, and in January, Audio!

Plus the Scene in Bookselling Now

To Those on the Vietnam Wall on the Mall

and their countless Vietnamese counterparts.

It did not have to happen.

—- The Dedication

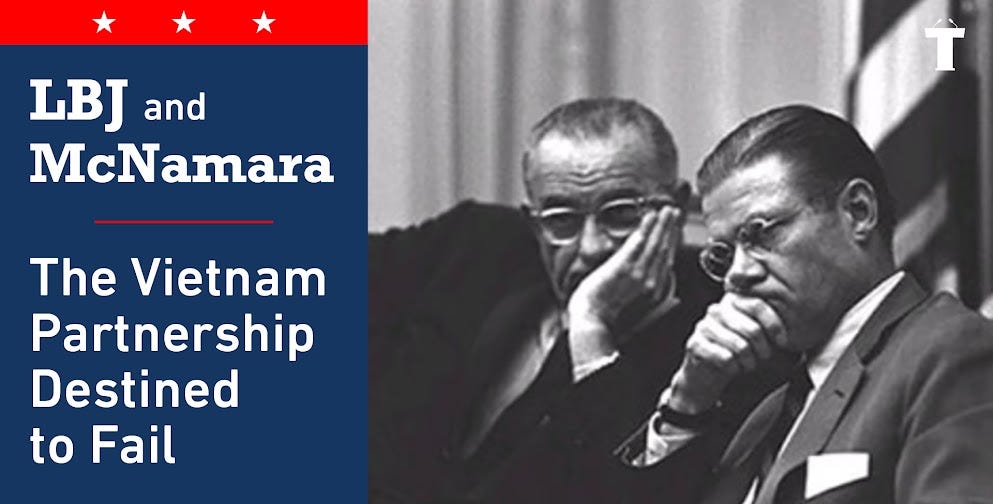

The Substack series called LBJ and McNamara: The Vietnam Partnership Destined to Fail is available everywhere as a book, reasonably priced at $17.95 and as an ebook from Amazon, BN.com, and elsewhere at $8.99.

Simon & Schuster will be releasing an audiobook in January that will include a bonus of two hours of McNamara with me devising what he wanted to say in his book In Retrospect, an unusual glimpse into the editing process of a controversial but in its way historically important memoir about the debacle in Vietnam, for which he was considered responsible.

(And in the aftermath of the reelection of Donald Trump to the presidency, it seems relevant to reflect, after a half century, on how another era of upheaval in American history happened and was handled.)

The purpose of this piece is to explain how this book fits in today’s publishing and bookselling world, which has changed more than readers may realize. Buying a book today should no longer be the challenge it was when the prevailing thought for anything other than bestsellers was “I’ll see if I can find it.”

The book in print is available at any retailer that sells books — but you’ll have to ask for it to be ordered, using the title, the author’s name, or the ISBN identifier, which is 978-1-953943-55-2.

Why?

Because it will almost certainly not be on bookstore shelves, where space is always tight. The publisher, a small independent called Rivertowns Books fulfills orders efficiently and places the book into every database — but does not do the in-store solicitations by sales reps that were for so long the way bookstores chose what to sell. They are still done, but mainly by larger publishers.

To underscore the point, which is crucial: the book is available everywhere and is featured in vast online catalogues, the best known of which is Edelweiss, a digital database founded about twenty years ago and used by most stores. This is a promotion tool, offering advance copies which are then ordered from distributors.

The “Big Five” publishers, as they are known, have the highest profiles in stores. They are Penguin Random House (owned by Bertelsmann, a German company), HarperCollins (owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation), Simon & Schuster (recently acquired by the private equity firm KKR), Hachette Book Group (owned by Vivendi, a French company) and Macmillan (owned by Holtzbrinck, a German company).

These five publishers tend to dominate the bestseller lists and generally pay the largest advances (guaranteed author payments), which are still regarded within the industry as the measure of a book’s presumed worth and potential.

Next are the independent publishers of some scale, including W.W. Norton, which is employee-owned; Bloomsbury, British-based and the originating publisher of the lucrative Harry Potter series; Scholastic, known for children’s books; and Grove Atlantic, which has defied the odds by making savvy selections.

The next tier down in size are the feisty (and therefore usually admired) publishers like Graywolf Press in literary works and Melville House, mainly publishing provocative nonfiction.

Many small publishers are for-profit entities — not a business model for the faint of heart. There are, of course, a good number of nonprofit university and academic publishers and thousands of micropublishers coming and going in a churning marketplace.

Finally, and least understood, is the range of publishers once derisively known as “vanity presses,” because the authors paid to have their books published. These have now evolved into an enormous self-publishing industry, in which anyone — anyone — can write and publish a book, usually by paying all or part of the cost of getting it released. My guess is that hundreds of thousands of books are published this way each year, selling anywhere from a few copies to family and friends to millions in categories like science fiction or “romantasy.”

The conventional belief is that consumers do not pay as much attention to the name or reputation of the publisher as the publishers would want. Instead, what is essential to selling books for them to be visible to consumers, the process called “discovery.”

Today’s world includes traditional media publicity, broadcast and reviews, although they generally have less impact than they used to. By any current measure, social media (essentially twenty-first-century word of mouth) like TikTok et al. are the most powerful.

Probably the greatest surprise of the modern era is that the overwhelming majority of books are still sold in print, around 70 percent. Digital or ebooks, once thought to be the inevitable leading format, amount to about 20 percent, with audio at 10 percent and growing faster than the other ways books are read.

The majority of book sales — to the consternation of everyone else — are on Amazon, where books can be ordered in print, digital, or audio and delivered overnight or immediately, usually at lower prices than standard retail.

Barnes & Noble, the largest of the chain stores, has revived in recent years under its CEO, James Daunt, opening and redesigning stores and updating the selection of books featured on its shelves. The range is even greater at BN.com, its online outlet.

The independent bookstore sector, almost always captioned as “beloved” or “revered,” is relatively small — around 10 percent of total sales. These locally owned stores are what people consider their favorite way to browse, where they engage with staff and visiting authors and increasingly spend time in the stores’ cafes. With Amazon and online ascendency, the “indies” were thought to be endangered, but the best of them have found their place in their communities as destinations and civic assets.

One enduring mystery for me is that the indies have never figured out how to sell ebooks. There is no real way to buy ebooks from them, which in turn drives consumers to Amazon and its Audible subsidiary. And in too many stores, buying books from a smaller publisher (like Rivertowns) demands persistence by the customer when the clerk is unfamiliar with the imprint, the author, or the title and says so.

My long-held belief is that when people enter a store and ask for a specific book, they should never be allowed to leave without at least ordering it and arranging for it to be delivered or picked up. If frustrated, the consumer will go to where the book can be had — which is mainly Amazon.

You may feel that all this marketplace description is more than you need or want to know.

So I will repeat the basic fact of this piece. LBJ and McNamara: The Vietnam Partnership Destined to Fail is available for sale. If interested, just order or ask for it. And if you find it worthwhile, please tell your friends.

**********************

“Insightful and informative…benefits from Osnos’ unique insights.”

—Kirkus Reviews (Starred review)

LBJ and McNamara: The Vietnam Partnership Destined to Fail describes how decisions about policy strategy were made in the Vietnam era —which in the aftermath of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and Ukraine and Gaza are worth knowing about now. The re-election of Donald Trump to the presidency certainly assures a period of upheaval in global affairs. The imperfections and consequences of decision making are always much clearer “In Retrospect.”