In the Garden of Memory

Part Four: Flt/Sgt Jan Ryszard Bychowski

The New York Times, Tuesday, May 30, 1944

New York Flier Is Killed

The Polish Telegraph Agency reported yesterday in a London dispatch that Sgt. Jan Bychowski of 49 East Ninety-sixth Street, New York, had been killed in action last week over Germany. He was the navigator of a Polish air force bomber. The son of a Polish psychiatrist, Dr. Gustav Bychowski, the flier came to the United States with his father after the German invasion of Poland. He volunteered for the Polish forces and trained in Canada before going overseas.

***************************************

Jan Ryszard Bychowski was born in Vienna in 1922. His father, Gustav, was there studying psychiatry with Sigmund Freud, on his way to becoming a prominent psychoanalyst in Poland and then for decades in New York. Taking advantage of the city’s nightlife, he married Ellen, a “music hall dancer” according to the brief description that In the Garden of Memory gives her.

The marriage did not last. In the 1940s, Ellen was living in Buenos Aires with her partner, Zosia, and sent affectionate letters to her son, Rysz, then serving with the Polish forces in Britain’s Royal Air Force. Written in English to get past censors, she wrote in May 1943: “My dear precious boy, I am so happy of your letters and beg you above everything else to take care of yourself, so that we may find you healthy and victorious back home…always your Ellen.”

She would never see him again.

Gustav’s second wife was Maryla Auerbach, “elegant. pretty and well educated” and “from the rich Jewish plutocracy.” In the Garden of Memory observes that she was “certainly a much more suitable wife for a renowned Warsaw psychiatrist.”

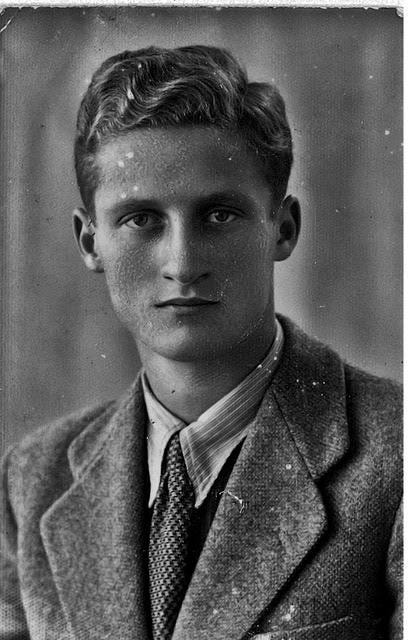

Among the many relatives Joanna Olczak-Ronikier writes about in her book, Rysz stands out as heroic, a martyr of course, but also for his charm and talent. Joanna’s chapter about him is called “The Boy from Heaven.”

Although only twenty-two when he was killed, he left behind a remarkable collection of writing, journalism, essays, and fiction, curated by his family and donated to the Jewish Historical Society.

I was especially struck by this item from “The “March of Time,” a national radio broadcast, on July 16, 1942, produced by Time Inc. and hosted by Westbrook Van Voorhis:

Van: This week from Canada…A twenty-year-old Polish youth who had come 20,000 miles from bombed-out Warsaw…stands at our March of Time microphone…about to leave on the last lap towards his destination. Journey’s end for him is in the air over Europe, raining death on the Nazi conquerors of his country, Richard Bychowski.

Richard: I came here tonight because I wanted to say goodbye to a fellow countryman of mine in exile in the United States. He was the composer of the music the orchestra is now playing. His name, Jan Ignace Paderewski. His temporary address…Arlington National Cemetery.

Goodbye, Mr. Paderewski…it is fitting that you are near the great George Washington. Each of you was his country’s first leader when that country gained its freedom and the day will come again when our Poland will be a free and beautiful land.

The full interview in Rysz’s voice is here

****************************************

Rysz (I never heard him called anything else) graduated in May 1939 from the Stefan Batory High School. Batory was a King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania in the 1500s, and his name is featured on monuments, streets, and schools all over Poland. The school was secular. In its records, Rysz was described as being of “Mosaic” origins, essentially a euphemism for Jewish.

A school friend, Koscik Jelenski, wrote years later that when he arrived at Batory, “I was immediately taken under the wing of a twelve-year-old boy (like me) lively, likeable blond boy with freckles and a snub nose… I remember that on the second day we ‘bribed’ a fat boy to whose two-person desk I was assigned. Rysiek sat in his place and from then we practically never apart.”

He describes how in their second year together Rysz got the answer wrong to a math quiz, and the class began chanting “Zyyt,” a slur of the word for Jew. When a “bloody fight began,” he continued, “only five of our thirty-plus classmates fought on our side.”

Rysz was a Polish patriot to his core, willing to give his life to his country’s defense. But the animus to Jews he encountered, even in his Polish flight unit, endured. Shortly before he died, he wrote to his father that he could never again live in Poland.

The summer after he graduated, he visited a place in the countryside where Joanna, then four years old, and my brother Robert, then eight, were on vacation. A photograph of them captured their unsuspecting innocence about the German invasion that was about to happen. It is the cover of In the Garden of Memory.

Rysz’s parents and his sister Monica, a toddler, left Warsaw when the war started, and only months later was he persuaded to join them instead of the resistance in formation. Because Gustav was already a famous psychoanalyst, the Bychowskis managed to get visas to the United States.

His parents went to New York, while Rysz enrolled as a student at the University of California’s Berkeley campus. The transcripts showed him as “a determined student as he encountered this new language and world.”

After a year, Rysz left for Ontario, where Poles were being trained for roles in the RAF. These Polish fighters in exile were considered exceptionally formidable. In the Battle of Britain in 1940, the Poles scored the highest kill rate against the Luftwaffe of any of the RAF units.

Rysz wrote of his growing commitment to aviation: “Up in the air there’s such perfect peace and quiet that you don’t want to return to earthly matters.” An article he wrote about the Poles training in Canada appeared in the New York Times, which was probably what led to his appearance on “The March of Time.”

He completed the training in December 1942 and went to Britain, where he qualified as a flight sergeant, flying as a navigator in bombing missions over Germany. Squadron 300, also known as the Masovian, had as its motto We Fight to Rebuild.

The squadron flew 3,891 sorties and spent 20,264 hours in the air, according to official records. It was involved in most of the major air offensives in the war. After Poland fell, aviators began to organize in France and relocated to Britain as the last country with the means to challenge the Germans. In all, 19,400 Poles served in the RAF, the largest non-British contingent. Two thousand were killed.

In the Garden of Memory’s description of Rysz’s life over the next two years reflected intensity and an effort to manage stress: “He went out on dates and to dances. He fell in love, and it was requited, writing his family, ‘You should be pleased, because she isn’t anyone’s wife…and there’s no question of matrimony.’” In September 1943 he was promoted to the rank of senior sergeant navigator.

But he felt growing bitterness about what he found among many Poles in the RAF regarding what was happening to the Jews in Poland. A letter to his father that was later reprinted in books and articles reflected his anger:

“My colleagues in the air force were either indifferent or openly pleased…For weeks on end I have seen boys smiling scornfully at the sight of headlines in the Polish Daily about the murder of Jews…I can see that there was nothing but indifference (in Poland) surrounding the Jewish people as they went to their death and contempt that they were not fighting, satisfaction that ‘its not us.’ The Jews could not escape because en masse because they had no where to go. Outside the ghetto walls there was an alien country, an alien population, and that seems to be the terrible truth…”

His conclusion:

“I hope I shall come out of the war safe and sound. I am already determined not to return to Poland…above all I’m afraid of knowing the whole truth about the reaction of Polish society to the extermination of the Jews…people who found it possible to ignore their destruction, occupy their homes and denounce or blackmail the survivors.

“That’s all I wanted to tell you, dearest Daddy.

“Maybe one day, years from now, I’ll go back there to gather material for a book about the Jewish tragedy that I would like to write.”

What happened on May 23, 1944, is summarized in a report in Britain’s National Archives: Rysz’s plane, an Avro Lancaster 1, left Faldingworth station at night with a target of Dortmund in Germany. The plane “suffered engine problems and turned back, jettisoning some of its bomb load to the sea. On return to Faldingworth, the Lancaster struck the gun butts.”

Two other members of the crew were killed also.

Rysz was buried in the Polish plot at Newark-on-Trent Cemetery.

The files at the Jewish Historical Society, so carefully maintained by Rysz’s family for decades, contain scores of condolence letters to Gustav and the family. I saw Gustav quoted as saying in his grief that if he had not had his daughter Monica, he would not have been able to go on.

In 1974, after Gustav’s death at seventy-seven, on a dance floor with Maryla in Morocco, Monica initiated the recovery of Rysz’s ashes, which were buried alongside his father’s headstone at a cemetery in Hastings-on-Hudson, outside New York City.

The next piece in the series will be the sequel to this story, and it will be, I assure you, surprising.