Excerpted from the book:In the mid-1930s, Maks Horwitz-Walecki, a member of the Polish Communist Party, had been living in Moscow for several years, working on the Executive Committee of Comintern, the international organization of Communist parties.

He and his wife Stefania lived at the Hotel Lux, which before the revolution had been one of the best hotels in Moscow. Since then it had lost much of its former splendor. Maks and Stefa’s rooms were not big, and when guests came to visit, camp beds were set up for them, with not much space to squeeze one’s way between them. Maks’s room was full of books and periodicals that did not fit on the shelves, so he kept them in the bathtub, which was never used because the bathroom had no hot-water supply. They washed in a communal bathroom shared by everyone on the entire floor.

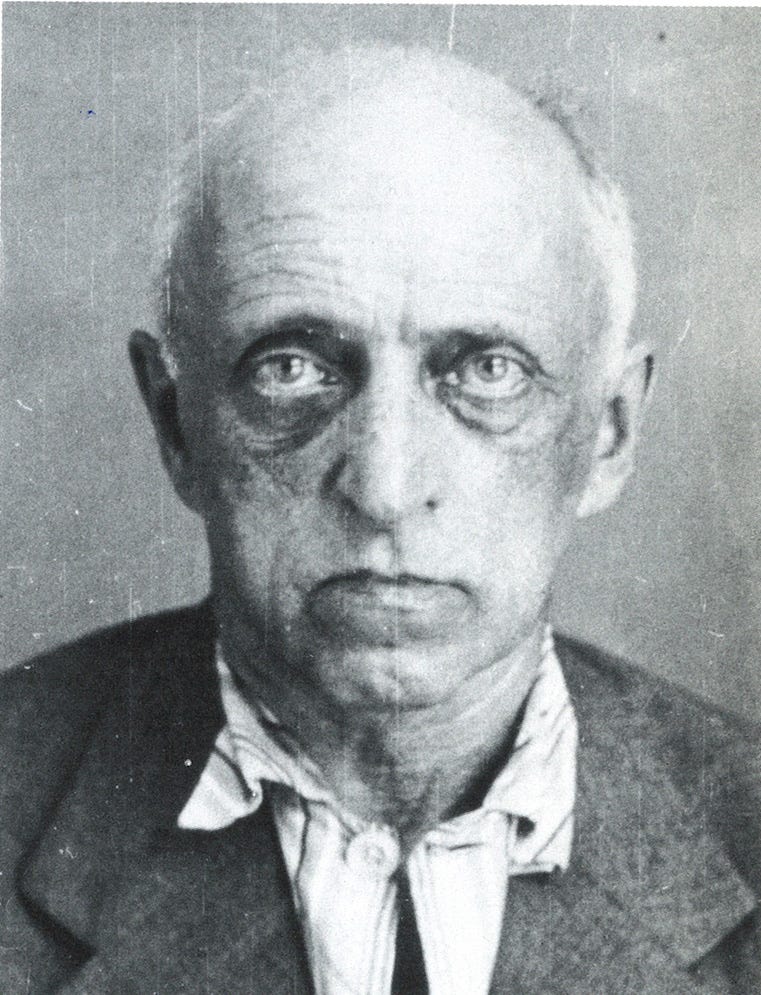

Maks was in a difficult situation. Stalin had not forgotten that Maks had dared to speak against him in the past, and he never forgave his opponents. The stronger Stalin’s authority grew, the worse Maks was rated within the Party apparatus, and the lesser a role he played in the public forum, the more unbearable and despotic he became within the family circle. His sister Kamilla respected his knowledge and authority, and was extremely fond of him, but with time they differed in their views more and more frequently. She resented his political disloyalties, and also the disorder in his personal life.

For he was leading a double life. Although he had been living with his wife Stefania for twenty-six years, in Moscow he had taken up with a girl almost a quarter of a century younger than himself. Józefina Swarowska, known as Josza, was an Austrian, the daughter of a famous Viennese prima ballerina. She was brought up in Vienna, in a wealthy home and a refined atmosphere. Her brother gained a higher education in music and became a well-known violinist, leader of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, but she had other ambitions. Very early on in life she became involved in communist activities; she met Maks at an international congress, and they fell in love.

She followed him to Moscow, and in 1932 she bore him a son, who was named Piotr for Maks’s tsarist-era pseudonym. Maks helped Josza to find work at the Comintern Secretariat, and put her up in a nice, two-room apartment on Gorky Street, but he never had the courage to legalize the relationship. He went on living with his wife, who eventually found out all about it and demanded a divorce. But Maks refused to give his consent. His grown-up children, Kasia and Staś, bore immense grudges against him. In their view he was making himself and his relatives miserable.

The year 1936 marked an intensification of the Great Terror. There were mass repressions and show trials. Some believed in the treachery of those arrested, others questioned it; while people consoled each other that it was a mistake that would be sorted out immediately, at the same time mutual mistrust and suspicions grew.

The Hotel Lux was gradually being depopulated. At night cars would drive into the courtyard. In their rooms people listened intently to hear which way the NKVD agents’ footsteps were heading. Sometimes a scream rang out, sometimes a woman or a child was heard crying. And then came footsteps on the stairs again, as the arrestees were brutally hustled away.

Maks’s niece Mania Beylin also lived in Moscow. Worried about the family, she would run to the hotel every day at dusk. Before entering the gate she would look up at Maks and Stefa’s windows to see if the light would be on. From day to day there were fewer and fewer lighted rectangles in the wall of the building.

On the evening of June 21, 1937, the light was on in the familiar windows. But the hotel seemed dead. There was no one on the stairs, and the corridors were silent and empty. Mania knocked at Stefa’s door, entered and found her lying in bed. She was having some sort of heart trouble and was desperately sad. Soon after Maks came into her room, changed beyond recognition. Usually full of energy and life, he looked like an old man now. His face was sunken, his lips compressed and his eyes dead. He sat on his wife’s bed and said nothing. Feeling at a loss in this atmosphere of hopelessness, but in an effort to help somehow, Mania went into the kitchen and made some tea. They gratefully accepted the glasses of hot tea, but could not swallow a drop of it. She tried to talk to them, but all her words died in mid-air. It was as if they were in another reality, another dimension, where she could not reach them. Time was passing, and midnight was approaching. She did not want to leave them alone, but finally Maks said: “Go now. It’s getting late!” And he hugged her goodbye.

Downstairs in the hall she saw an NKVD detachment coming through the hotel doors. “Who will be the unlucky one tonight?” she thought. First thing next morning she called Maks. His son Staś picked up the phone. “How’s your mother feeling?” she asked. “Don’t come here,” he replied, and hung up.

They had come for Maks at about two in the morning. Stefa, who could not sleep, decided to look in on her husband. She could hear men’s voices on the other side of his door. She tried to enter his room, but was not allowed inside. Instead she was brutally ordered back to her own room. According to the neighbors, Maks was taken away first, and then Stefa. Next a thorough search was conducted in both rooms. The books were thrown from the shelves, papers from the drawers and clothes from the wardrobes, as usual in such cases. Early next morning, worried that neither his mother nor his father was answering the phone, Staś ran to the hotel. When he saw what had happened, he tried to get some information about their fate, but no one was willing to tell him which prison they had been taken to, what sort of danger they were in, or what could be done for them. Neither influence nor personal connections were of any use. At that time people were disappearing without trace, as if they had never existed.

Mania later learned that when she saw Maks the previous evening, he had no doubt what was in store for him. He had already been “thoroughly investigated” earlier by the Special Control Commission attached to the Comintern. His closest collaborators and friends had interrogated him and had accused him of belonging to an “anti-Soviet Trotskyite group,” “counter-revolutionary activity,” “spying for fascist Poland” and other European countries as well. For three days he tried to prove his innocence, but the sentence had already been passed a long time ago, and at a much higher level.

He was told that he had been dismissed from the Party and was ordered to hand back his Party membership card. For a dedicated communist losing this document meant annihilation, civil death and spiritual bankruptcy. He had lost faith in the meaning of his entire life, and he must have sensed that he would soon lose his life as well. After all, he could see what was happening around him.

When Mania called the Hotel Lux on the morning of June 22 and heard Staś’s voice at the other end, she immediately understood what had happened. There was no way she could help. She had no influential acquaintances, and she herself was in a desperate situation. The Journal de Moscou, the French-language magazine where she worked, had been closed down and its editor-in-chief arrested. Since losing her job she had been giving math lessons, but then the Soviet authorities had withdrawn her residency permit. She would have to leave the USSR as soon as possible, but she could not go to Poland, as the Polish embassy had taken away her Polish passport because she was a communist. Thanks to the fact that her young son Pierre had been born in Paris she managed to obtain a French visa, drawn up on a scrap of paper because she had no travel document. All around her the situation was growing more and more dangerous. Leaving Russia was her final chance of salvation.

But she did still manage to seek out her uncle’s young girlfriend, Josza. She was afraid someone uncaring or malevolent would pass on the tragic news, and preferred to do it herself. She wanted to leave her some money, because she could tell that the girl would be in a difficult situation. Unknown to the rest of the family, who refused to tolerate the relationship, she had been to see Josza before, and was very fond of her. She could see how much Maks loved her and how affectionate he was toward his little son, whom they called Petya. She knew he must be worrying about their fate.

Josza and Petya were now living in a Comintern dacha in the Moscow suburbs. That evening Mania went there by train and got out at the small station. There were dozens of identical summer holiday cottages, with the same sort of curtains in all the windows and the same porches in front, with little tables set out on them. On each table stood a samovar, around which the holidaymakers were gathered, eating their supper. The air smelled of pine forest. From a distance she could hear the sound of an accordion and someone singing. It was a peaceful idyll, an atmosphere out of Chekhov, as if the echoes of all the dramas being enacted so nearby did not reach this far. But the carefree mood was just superficial. When Mania tried to find out where the Comintern house was, at the sound of her foreign accent fear appeared on the faces of the people she asked, and they fell silent. No one knew a thing, and no one was willing to talk to her. She was foreign, and that made her suspicious¾she could bring the all-pervading misfortune down on them. Finally someone very bravely whispered: “It’s over there,” and showed her the way.

She opened the gate. She could see people’s silhouettes in the illuminated windows of the villa. On the lawn there was a motionless white shape, like an elongated bundle. When she had gone a few steps forward, the shape began to move, and someone raised their head. It was Josza; she was lying on the grass, on a straw mattress. Beside her, wrapped in a blanket, little Petya was sleeping. She threw herself into Mania’s arms, sobbing: “It’s impossible! It’s not true! It’s a terrible mistake!” She already knew what had happened. Mania tried to comfort her, saying: “Of course it’s a misunderstanding! He’ll be back. He’s sure to be back.” And then she asked in amazement: “Why are you sleeping here on the damp grass and not in the house?”

It turned out that the Comintern authorities had acted very efficiently. They had instantly revoked Maks’s rights to an apartment in the dacha and had assigned it to the family of another top official. The new tenants had arrived that afternoon, brought the news of Maks’s arrest and told Josza to get out at once. Trembling all over, she had not had the strength to organize the move and did not even have the money for a ticket to Moscow. So they had agreed that she could stay until morning, but outside, not in the house. She and her son had spent the whole evening on the lawn, and then she had covered him up and cuddled him until he fell asleep.

Mania had to go home. The only thing she could do was wish the broken-hearted woman courage and offer her the money she had brought. Then she left them both on the lawn. Next day she and Pierre departed for Paris, and Josza and Petya returned to Moscow.

Josza never saw Maks again. None of the family ever saw him again either. The Polish Communist Party leaders were not given big show trials, and their sentences were not announced publicly. Instead they were liquidated on the quiet. Their relatives deluded themselves for years with the idea that they were still alive. However, they could not make any proper efforts to find out the truth, because they themselves were in prisons and camps under long-term sentences. They belonged to a special group of victims that bore the official title: “members of families of traitors to the fatherland.” By some miracle Josza escaped repression, though fate still had some trials in store for her and Petya too. But that is another story.

Coming tomorrow an audio version of the first three pieces about the book and how to pre-order..