In the Garden of Memory

Part Two: The introduction by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

This is the biography of three generations of a family, a remarkable family, by reason of the place and time in which they were born, but also in terms of character. Joanna Olczak-Ronikier has taken the trouble to investigate their lives and understand their decisions and emotions, resulting in a family saga that is as compelling as a novel. She starts with her great-grandparents, Gustav and Julia Horwitz (born in 1844 and 1845), and from the first challenge of Gustav’s early death, his relatives’ responses to the trials inflicted on them by their historical fate show unusual determination and courage. As I read about them I find myself returning to the old question, ‘Is man the product of his heredity or his environment?’

Many of the personalities in this family are strong-willed and rebellious, refusing to remain passive in the face of iniquity. The generation of nine siblings born to Gustav and Julia in just thirteen years (from 1868 to 1881) include Maks whose commitment to the communist cause was so singleminded that it led, through prison and exile, to a horrific death in Stalin’s purges; Kamilla, whose obstinate confidence in her own role in life led to a medical career but also prison and exile as another victim of Stalin; and Janina, whose creativity and fortitude helped her to found a great publishing house, to weather widowhood and save her immediate family from the Holocaust. What would their lives have been like if born in a different era, or in a different country? I suspect they’d have been just as stormy and productive in any situation.

But they happened to be born in Warsaw when it was still inside the Russian Empire, and they happened to be born into an assimilated Jewish family, educated and well-to-do, with opportunities but with the limitations imposed by the anti-Semitism that was deeply ingrained in Polish society. However committed to the noble cause of Polish independence, however refined and well-read, they were never entirely accepted by the Polish elite and could never be equal. Growing up with this sense of second-class citizenship seems only to have reinforced their determination to prove themselves to the world, and never to forget their mother’s instruction to keep their heads held high.

By taking the story of her family back to her grandparents’ generation, Joanna Olczak-Ronikier provides a lucid explanation of the position of assimilated Jews in Poland; we generally have some idea of the isolated and impoverished existence of Orthodox Jews in shtetls who were destroyed by pogroms, but fewer books focus on the sophisticated, urban Jews who had dropped religious practices and Yiddish, who joined the fight for independence and had refined literary tastes. Reading this book for the first time revealed to me a whole different stratum of Jewish society at the turn of the nineteenth century and helped me to understand attitudes to Jews in Poland in the twentieth, as well as Jewish attitudes to Poland. As the author has said: ‘This book was a way to say it: I do not have to be afraid any longer. It is an homage to a particular world the Polish intelligentsia of Jewish origin, people who have chosen to love Poland with a love that was not always a happy one, but that was always faithful.’

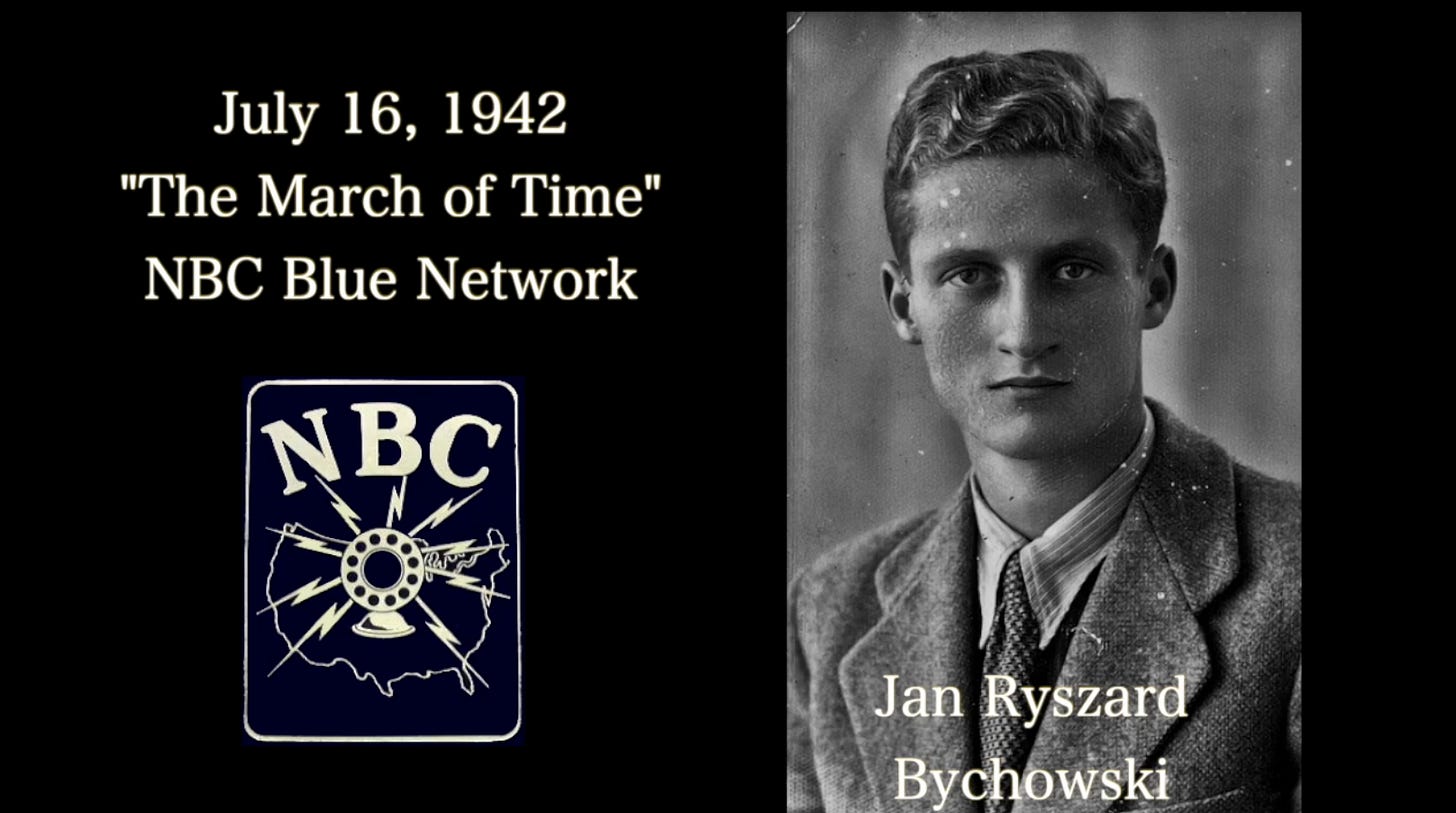

The next generation, mostly born in the first decade of the twentieth century, could profit from the advantages brought by Poland’s independence between the world wars, and started on successful lives and careers. But then they had to contend with the tragedy of the Second World War, the Nazi and Soviet invasions of Poland, the Occupation and the Holocaust. How on earth does anyone survive sudden invasion, bombardment from the sky, brutality in the streets, and an orchestrated genocidal campaign? It is impossible to imagine. Once again, the members of this family showed their grit, backed also by their firm family solidarity and devotion to each other, and by escaping or hiding in harrowing circumstances most of them survived. In the next generation Ryszard Bychowski began a promising career as a writer, and after enduring the ordeal of a refugee, refused the safety of California. Instead he became a war hero who fought and died as a navigator on an RAF bomber at the age of 22. His letters are poignant testimony to that family tenacity, as well as to the terrible time in which he lived. Most of the surviving descendants of Gustav and Julia went on to resume their careers and build new, fruitful lives, whether still in Poland or abroad.

The generation of Polish Jews that survived the Holocaust is dwindling. The child survivors are now in their nineties. Every story is important, shocking and different, and needs to be recorded. Not every memoirist is as skilled a writer as Joanna Olczak-Ronikier, who in this book provides a first-hand account of what it was like for a child, understanding very little, but sensing a lot, to be moved urgently from place to place, hidden in altars and disguised as a Catholic; just as her forebears had learned in childhood to conspire against the Russian Empire, she had to dissimulate from an early age, and know how to keep her mouth shut. What a challenge for a small child. Here she pays moving tribute to the incredibly brave individuals, Poles who were not Jews who saved her and her mother and grandmother at great risk, and sometimes at the cost of their own lives. When she asked Jerzy Żurkowski why his family had consciously risked death by hiding Jews, he explained their conduct as ‘common decency’. Who can be sure they’d behave so decently to strangers?

I have met several descendants of Gustav and Julia, and can confirm that they are extraordinary people with strong personalities. They’re creative, generous, defiant and determined. They know what they want to do and nothing will stop them from achieving it. They place great value on genuine friendship and commitment. And as the epilogue describing their historic gathering in 2000 shows, they have an unshakable sense of family loyalty. Their refusal to be repressed is inspirational. Since the Holocaust two more generations have grown up and are living productive and original lives, and since this book was first published twenty-four years ago, a whole new generation has been born, giving their story a happy ending. I shall override their dislike of sentimentality to say: ‘Long live the heirs of Gustav and Julia Horwitz!’

Antonia Lloyd-Jones has translated works by many of Poland’s leading contemporary novelists and reportage authors, as well as classics, biographies, essays, crime fiction, poetry and children’s books. Her translation of Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by 2018 Nobel Prize laureate Olga Tokarczuk was shortlisted for the 2019 Man Booker International prize. For ten years she was a mentor for the Emerging Translators’ Mentorship Programme, and is a former co-chair of the UK Translators Association. Her recent publications include translations of The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story by Olga Tokarczuk, Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda, and as compiler and co-translator, The Penguin Book of Polish Short Stories.

To see the video click here Ryszard Bychowski

Ryszard is one of the many remarkable people you will meet in Joanna Olczak-Ronikier’s prize-winning book In The Garden of Memory -A Family Memoir. This is an interview with him on “The March of Time” radio broadcast while he was in Canada training to be a flier in the Polish branch of Britain’s Royal Air Force.

More than 25 years ago, you published my family memoir. It changed my life. This one sounds remarkable. I hope you are well, Peter.