Janet Cooke is Now 66

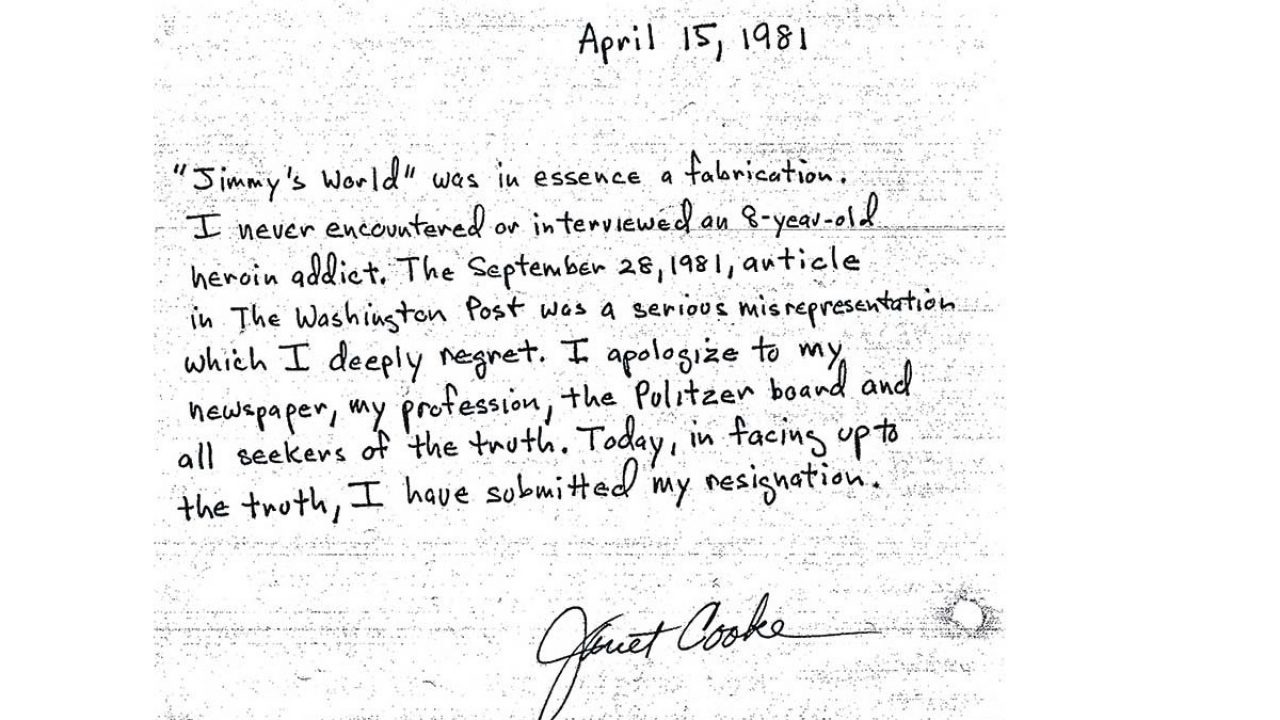

In the spring of 1981, Janet Cooke received journalism’s ultimate accolade, a Pulitzer for “Jimmy’s World” which had been a front-page feature in The Washington Post the previous September. It was beautifully written at over 2000 words. It caused D.C. authorities to launch a search for Jimmy which ended when it was determined that he had “died”.

There was no Jimmy. Cooke made it up. As fiction, it might have been hailed. As a newspaper story it was a disgrace. Cooke left The Post and essentially disappeared, an ignominious figure in the modern history of journalistic ethics.

Cooke was definitely a “fabulist”. Her resume was inflated. She did not graduate from Vassar. She was a BA from the University of Toledo. Other details were enhanced to make her, as a candidate for a job at The Post, irresistible. She was Black, elegant and seemingly self-assured. She was what we describe these days as a millennial, a generational trope that supposedly accounts for certain behaviors.

The scandal was especially public because The Post was still basking in the aura of its Watergate triumphs and the star power of, among others, Bob Woodward. He was Cooke’s boss in the Metro section of the paper which guaranteed some wider satisfaction at seeing The Post brought down a peg.

As I recall, I only had one encounter with Cooke. I was waiting for my car at a garage near the office. At the time I was the paper’s national editor. Cooke was also there and with a smile said that her goal was to work for me. I doubtless said something meant to be encouraging.

So, I did not know Cooke, or her personal story, or her personal motivations or the impact of this professional disaster on the rest of her life.

On one of the social media sites, I saw a reference to Janet’s World: The Inside Story of The Washington Post Pulitzer Fabulist by Mike Sager, who was a reporter at The Post, a boyfriend of Cooke’s and a much-published author. This self-published book of 72 pages, for sale on Amazon is essentially a GQ profile of her written in June 1996 and update for the Columbia Journalism Review in 2016.

I was startled to realize that it has been forty years since “Jimmy’s World” and the aftermath.

We aren’t told where Cooke is now. In the 2016 piece Sager writes:

I am nominally in touch with Cooke via email. I don’t think I will betray her trust by reporting that she is living within the borders of the continental United States within a family setting and pursuing a career that does primarily involve writing.

Elsewhere Sager reports that Cooke was married, lived in Paris with her husband and later divorced. She has worked in retail and at one time, sold her story to Hollywood for a movie that was never made.

The fact that Cooke is now eligible for social security, living somewhere basically incognito gave me pause. Why all those years ago did this happen to Cooke? Why was it allowed to happen by some of the very best journalists of that era at The Post? Did she deserve to be from all accounts, destroyed? And what about now?

Will Cooke’s next public appearance be her obituary? If this wasn’t a story from decades ago, would the media be searching for her? After all, she has many of the aspects of today’s fascinations. A woman, African American, and from her photos at the time, glamorous. She sinned and suffered. Did she deserve the punishment?

The question I was left with was, what is the statute of limitations on transgressions? This is an especially relevant topic now when, a 27-year-old woman of color Alexi McCammond was hired and immediately resigned as the editor of Teen Vogue for tweets she had written as a teenager and for which she had apologized in recent years.

All I know about Janet Cooke in 1980–81 or later comes from Sager’s account. I have not pressed further with any of the people she mentions as involved at the time. So, I cannot vouch for his portrayal. It certainly seems precise, unsparing and empathetic.

What are the takeaways for today’s sensibilities and standards?

Janet Cooke had a very complicated sense of race and womanhood. Her father, according to Sager, was ambitious for his offspring and a tyrant. She was raised to be a Black woman in an integrated world of private school. She spent one unhappy year at Vassar before returning to Toledo. Her brother graduated from Brown.

She was clearly gifted as a writer and yet was profoundly insecure. Her self-doubts played out in the disarray of her personal life in Washington, which was apparently not visible to others in the Post newsroom.

There was a suspension of disbelief about the story. The scourge of drug addiction, particularly in Washington’s Black community (the city was then 70 percent Black) was undeniable. And to put it simply, her editors took the position that her piece was “too good to check” as notorious a principle as there is in journalism. The Post was known for favoring what were called “holy shit” stories of the kind that particularly pleased the great editor, Benjamin C. Bradlee.

In today’s world, the measure of “holy shit” stories tends to be the clicks they generate—a form of impact that can be as corrupting as wanting a dramatic front- page story was for Cooke.

And then there is the prevalence of disinformation. We are inundated with information from many more sources than we were 40 years ago, largely because of the internet and social media. The drive to curtail disinformation is a major theme of journalism now, as well as in politics, and life in general. “Jimmy World” was by today’s standards unusual but not unique — a concoction of what might reasonably be but is not.

Finally, was Janet Cooke rightly punished for life? She was a fine writer with a vivid imagination. She was young, immature and not properly supervised by her supposed mentors.

Janet Cooke’s literary falsehoods were inexcusable, and a one-way ticket to misery. At what point is redemption acceptable when absolution is not possible?