For people in the business of gathering and delivering the news, the news is terrible. Layoffs, cutbacks, buyouts, closings, news deserts. The headline of a recent appraisal of the media by The New Yorker posited “Extinction.”

But wait! Billionaires are buying in (with finite patience). Philanthropists are stepping in (up to a point). All across the country, small and not-so-small nonprofits are in business, at least until their start-up support runs out. And even some taxpayer money is in the mix (though that can be tricky to accept).

Local, national, and international news outlets — watched on screens in your hand, on your lap, on your desk, or on the wall — are in fierce competition. They are expected to pay their way (and more), and if they don’t, the solution is to cut, cancel, or succumb to the lowest common denominators of bleed-and-lead. If everything is “breaking news” or a “crisis,” what really is happening?

A caption of “mayhem” or “chaos” would seem to apply. In fact, we are inundated with news, measured in output of all kinds, telling us what is going on, for better or worse. But it is the business — the dollars-and-cents business of journalism — that is in such a mess.

Why?

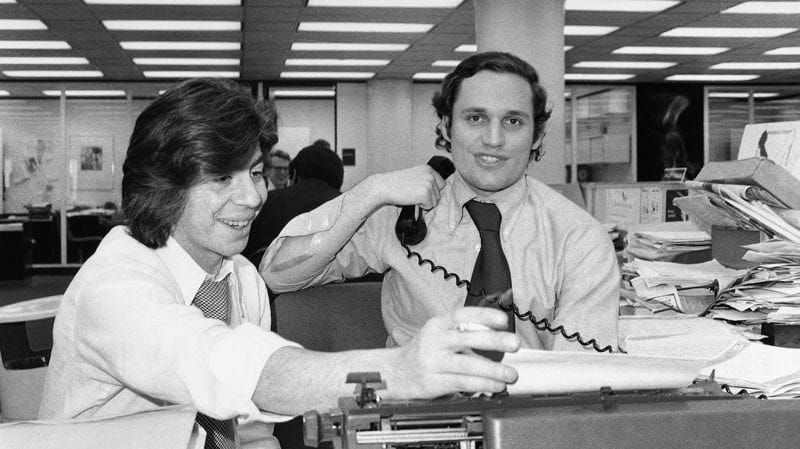

Katharine Graham was the esteemed proprietor of The Washington Post Company when it owned The Washington Post, Newsweek, and enough other enterprises to be trading at $800 and more per share, for which you didn’t actually get the possibility of voting control. She once described the strength of the newspaper (and by extension, the news business generally) as: “Woodward & Bernstein and Woodward & Lothrop” — the great Watergate reporting team and the great downtown department store.

What she meant was that the news business operated in two distinct lanes: the content it reported and the advertising revenue that paid for the content. The business side, as it was called, was responsible for paying the bills — supported, in the case of newspapers and magazines, by subscriptions, which was a valued but less lucrative factor.

And then, in the twenty-first century, advertising fundamentally changed: To this day, most of the vast revenues of Alphabet and Meta come from a different kind of advertising, shaped by algorithms to the extent that if you once click on, say, a shoe, you’ll be getting pitches for shoes, shoes, and shoes.

I should say here that for the people in the news business this is no revelation, and the formula for how advertising revenues are apportioned is a tug-of-war that is overwhelmingly on the side of big tech and the internet-based sites like YouTube (owned by Alphabet) and Facebook (owned by Meta). These companies contend that they link and send people to the originating news sites, though in fact they do this much less often than they used to. Why bother?

Apple sells enormous quantities of goods. Amazon sells almost everyone pretty much everything. Microsoft dominates software. The news business manufactures news. What has become indisputably clear is that getting audiences to pay for it on a scale that can sufficiently cover the costs of gathering it is very, very hard.

(I am going to use data in the next two paragraphs that I found online. My sense of numbers is that vouching for them, unless you were the one who actually compiled them, is risky. But let’s agree that they are close enough to be taken seriously).

Among news businesses, The New York Times is considered singularly successful, with total global subscribers, the great majority of whom are digital, of 10.36 million, and that is on a sustained upward swing. The Times’s earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) for 2023 was more than $336 million. What I have seen reported is that about 80 percent of its revenues come from subscriptions and 20 percent from advertising — the complete reverse of the split at the turn of the century.

Alphabet’s reported profit for 2023 was $73 billion – which is to say more than two hundred times that of The New York Times.

So where does the money for news come from? Here is my list of sources:

· Subscriptions

· Memberships

· Advertising, aka underwriting and sponsorships

· Philanthropy

· Events

· Data sales

· Partnerships

· Alliances

The challenge is to devise a means of combining these in a way to reach what might be called the “holy grail”: sustainability, defined as “revenue that can be maintained at a certain rate or level.” This model has yet to be devised. With so many different sources, one set of fundraising skills may not mean that you have as many as you need. Moreover, people who gather the news are not by instinct and experience necessarily destined to be successful at creating or sustaining businesses.

And businesspeople with bottom lines to meet — getting enough money to pay for everything — tend to find the news side more hopeful than realistic.

This conundrum is being considered at scheduled meetings, summits, conferences, and retreats, where practitioners in discussion enhance solidarity, even as practical solutions have so far been elusive. There is money to be spent — a philanthropic consortium called Press Forward recently announced a fund of $500 million to start with, an important initiative. Similarly, the American Journalism Project raises and dispenses million of dollars and expertise to nonprofits. (Its CEO, Sarabeth Berman, is my daughter-in-law, and she is as formidable in that role as she is irresistible in many other ways.)

So, back to the top. The business of news is in the enormously complicated process of reinvention, and how that will happen — and it must — is the news story yet to be written.