From the start of the twentieth century, the Nobel Prizes have honored those who have “conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.” The awards tend to be for lifetime achievement in science, literature, and economics. The peace prize, however, often goes to people and movements with ongoing missions – which can be risky.

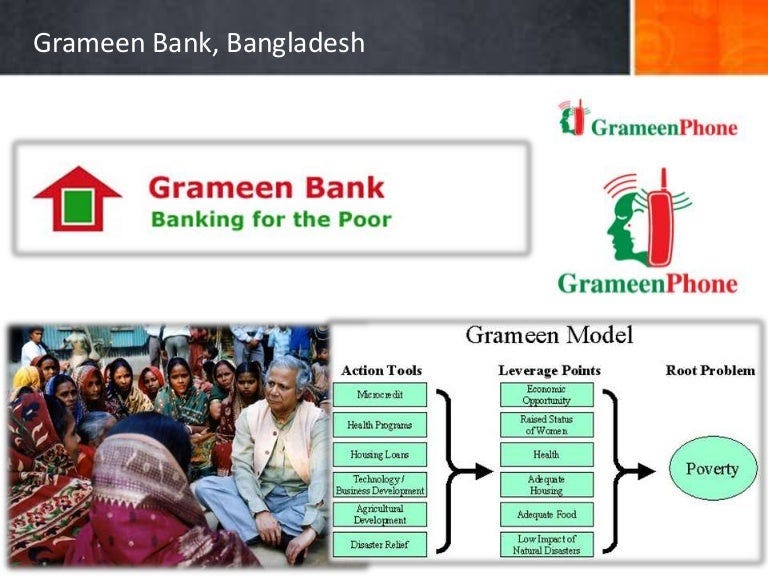

In 2006 Muhammad Yunus received the Nobel Peace Prize, along with Grameen Bank, the bank he founded and which pioneered microcredit in Bangladesh. Today he lives in Dhaka, where at age eighty-three he works in support of a now-global movement to make small loans, the majority to women, to establish businesses and pay back these loans from revenues.

His efforts, however, carry an enormous burden. He is currently appealing a jail sentence for a bogus labor fraud conviction; and in March he (along with colleagues) will face even more serious charges on money and management issues; and he is parrying upwards of 170 other lawsuits and administrative harassments unleashed by Bangladesh’s autocratic and just-reelected prime minister, Sheikh Hasina. Here is the powerful letter on his behalf released Monday and signed by hundreds of the world’s most prominent notables.

Martin Luther King Jr. received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 and was assassinated three and a half years later. Andrei Sakharov received the prize in 1975 (the Soviets wouldn’t allow him to travel to Oslo to accept it) and was sent into internal exile with his wife, Elena Bonner, in 1980. Aung San Suu Kyi of Myanmar is again under house arrest, after a bumpy period in politics. The teenage activist Malala Yousafzai fled Pakistan after she was shot, and soon thereafter received Nobel Peace Prize for her activities. She now lives in the U.K.

Yunus, who also received the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009 and the Congressional Gold Medal in 2010, has written four books, starting with Banker to the Poor: Micro-Lending and the Battle Against World Poverty and continuing with Creating a World Without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism; Building Social Business: The New Kind of Capitalism That Serves Humanity’s Most Pressing Needs; and A World of Three Zeros: The New Economics of Zero Poverty, Zero Unemployment, and Zero Net Carbon Emissions.

PublicAffairs published them all, which meant that we came to know Professor Yunus (I don’t recall ever calling him anything else) as much more than a man to be admired. We were collaborators – which brings you close enough to gauge the personal characteristics of a humanitarian icon. Suffice to say that after working with Yunus, our publicity director quit and joined Grameen in Bangladesh.

The origin story of Grameen dates to Yunus’s career as an economist in Bangladesh in the 1970s, when he came to believe that microloans to the poor, almost all women, would enable them to create businesses, usually as a collective, that would repay the credit. When I first learned of Grameen in the early 1990s, I was impressed but inclined to wonder whether the concept was really as solid as it seemed.

Bangladesh had been East Pakistan after the partition of India in 1947. In 1971, a war of liberation was waged, and the nation of Bangladesh -- led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (the father of the current prime minister) and the Awami League -- was established. It became one of the world’s most populous countries and one of its poorest. In the midst of other global priorities – the Cold War, the overture to China, the Vietnam war – and America’s relations with India and Pakistan, Bangladesh was sidelined.

The U.S. Under Secretary of State U. Alexis Johnson notoriously called Bangladesh “an international basket case,” to which National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger replied, “But not necessarily our basket case.”

The population of Bangladesh is now about 170 million people. Its economy has steadily improved, despite the enormous impact of weather-related catastrophes and its dependence on farming. It is now one of the main suppliers of low-cost clothing and household goods and is among countries considered lower middle income – with a monied class but better circumstances for the majority.

Without question, the successes of Grameen Bank and other Grameen enterprises have been essential to that progress.

Which is where the story takes an increasingly dark turn. Sheikh Hasina and her Awami League’s victory – in an election boycotted by the opposition party -- giving her a fifth term confirms Bangladesh’s “transition from a flawed but competitive democracy to a de facto one-party state, albeit with electoral democratic trappings,” as The Economist put it. And one of the main features of Hasina’s authoritarian politics is her campaign against Yunus personally and against all of the Grameen enterprises, with the intention of transforming them to her benefit or demolishing them altogether. If she succeeds, Grameen would be rendered a facsimile of Yunus’s vision.

Hasina’s enmity surfaced when the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize affirmed Yunus as an internationally recognized innovator, a celebrity – arguably Bangladesh’s most famous citizen.

Yunus briefly considered entering politics, which was enough to inflame Hasina, who began an enduring cycle of harassments that have threatened Grameen’s continuing work and doubtless made life for Yunus increasingly stressful. But he has stayed in Bangladesh, defended himself, and managed to hold off the most draconian of Hasina’s ploys.

Meanwhile, Grameen America, for which Yunus is the co-chair, is a nonprofit financial services company that has made nearly one million loans to lower-income women, amounting to more than $3.5 billion, according to its website.

The great nations of South Asia -- India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh -- are prone to nationalist leaders and turbulent politics. Professor Yunus has been swept up in that, but his vision and what it has achieved is of immense and immutable benefit to humankind.

Most thoughtful and revealing about a man and part of the world so often overlooked and overshadowed by events elsewhere.