A starred Publishers Weekly review of Craig McNamara’s book Because Our Fathers Lied: A Memoir of Truth and Family, from Vietnam to Today called it “stunning, deeply personal . . . reveals reams of hitherto unreported details . . . and reaches a depth of understanding . . . that no previous book . . . has achieved. This is a must read.”

I was surprised and intrigued. I had not known of the book. I was the editor of Robert McNamara’s memoir In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam and two more of his books with much the same message, advocating against wars in the future – a hopeless pursuit.

Craig’s book indicates that he conducted interviews with several of his father’s biographers and with Errol Morris, the filmmaker whose documentary The Fog of War (based on the “lessons” of In Retrospect) won the 2003 Oscar for best documentary feature. In a follow-up interview with Publishers Weekly, Craig was asked how he feels about Vietnam today:

“I am not a person who lives by regrets, but I do have one: that my father didn’t fully apologize. I wish that he had told the people who served in Vietnam and said from his heart, ‘I am so sorry for your loss.’”

In the closing scene of Morris’s documentary, after what, on the whole, is a representative if not sympathetic portrait of Robert McNamara in his final years, Morris asks if Bob is ready to apologize for the war. “Don’t you think I’ve said enough?” is essentially the response.

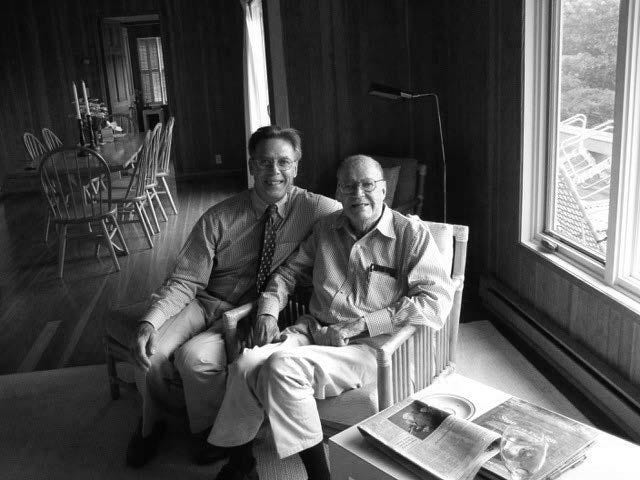

Having worked closely with Bob on his books for almost a decade, I came to know him well. I have hours of recordings of our interviews for In Retrospect, in which we explore his evolving sense of the war’s trajectory. In one of our last sessions, Bob said this, which appears in the book’s preface:

“We of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations who participated in the decisions on Vietnam acted according to what we thought were the principles and traditions of this nation. We made our decisions in light of those values.

“Yet we were wrong, terribly wrong. We owe it to future generations to explain why.”

A few pages later, he writes:

“Vietnam and my involvement in it deeply affected my family, but I will not dwell on its effect on them or me. I am not comfortable speaking in those terms; by nature, I am a private person. There are more constructive ways to address our nation’s Vietnam experience than excessively to explore my own pride, accomplishments, frustrations, and failure.”

The book has three fragmentary mentions of Craig. Bob recalls finally seeing Craig play football at St. Paul’s, a New England boarding school, and being summoned to take a call from President Johnson. He reports that his wife, Margaret, developed a debilitating ulcer, as did Craig. And finally, he describes a mountain hike and road trip father and son took in 1967. Bob helped Craig financially to launch a walnut farm in California, which became a considerable success.

Craig’s book speaks eloquently for itself. Instead, I want to try to answer the question that over and over I asked myself and Bob as we worked together: Why was it impossible for him and his colleagues to accept the reality that the war could not be won?

This was a very hands-on partnership. Bob’s researcher, Brian VanDeMark, and my young editorial colleague Geoff Shandler knew that this was an important book and bound to be controversial. And it was. It became a #1 New York Times bestseller. There were outraged commentaries demanding to know why, if Bob knew in 1966 that the war could not be won, why it took him until 1995 to acknowledge that publicly. That said, anyone who spent time with him after he left the Pentagon in 1968 knew his anguish about the impact of the war and what it had meant to his family.

McNamara was not alone in his early recognition of the war’s destiny. In Julia Sweig’s fascinating account of Lady Bird Johnson’s Diaries, she writes repeatedly of how Vietnam devastated Lyndon Johnson personally, from his early days in office, fostering a depression to which she attributes his death only four years after he returned to Texas. And yet these men (and they were all men) who in David Halberstam’s famous phrase were “the best and the brightest” of their time could not publicly accept what they knew to be the case about the conflict. Today, more than fifty years later, an autocratic unified Vietnam is a dynamic nation and considered a reliable Asian partner to the United States. I spent two years there as a reporter during the war and have visited the country twice since. The “American” war is a distant memory there, and here we relive it relentlessly wherever the American military is deployed, usually as a reference point for U.S. shortcomings.

Our wounds have not healed, which is why Craig’s book will resonate in the way early reactions to it suggest.

My own answer to the question has two parts:

(1) This was a generation who came of age during World War II and its aftermath. The triumphant battle against fascism morphed into a nuclear armed standoff with the Soviet Union, which was seen as a mortal struggle for the future of civilization. This made the concept of failure in Vietnam essentially impossible. Of all those responsible for the war in those years, only Robert McNamara ever publicly tried to explain the disaster. In my memoir An Especially Good View: Watching History Happen I tell the story of how John F. Kennedy Jr. shocked the audience at Time magazine’s seventy-fifth anniversary gala in 1998 by paying tribute to Bob for his unique courage and the way he was denounced.

(2) The men in power in that era tended to deflect emotion in a way that today would seem more self-consciously stoic than sensible. Alcohol was at the ready to ease stress from the excesses of ambition, work and pride. The first U.S. secretary of defense, James Forrestal, jumped from a window soon after he resigned. Frank Wisner, one of the charismatic founders of the Central Intelligence Agency, committed suicide in his mid-fifties. Another founder, Desmond Fitzgerald, dropped dead on a tennis court at a similar age.

In today’s world, would Robert McNamara be able to apologize for the war, as his son wanted him to? Could he have brought the war to an early close? Have we heard spoken regrets from George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, and others about Iraq and Afghanistan? Did Donald Rumsfeld apologize?

I spent enough time with Bob McNamara to know that had he found a way to do better with Craig; his daughter, Kathy; and his devoted wife, Marg – and perhaps do better by the country he served – I suspect he would have done so.

.