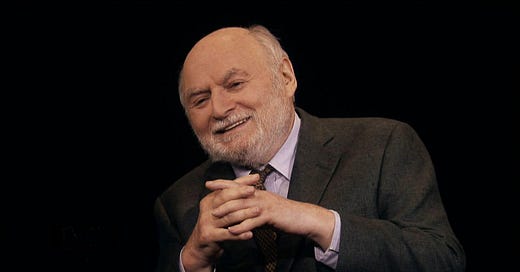

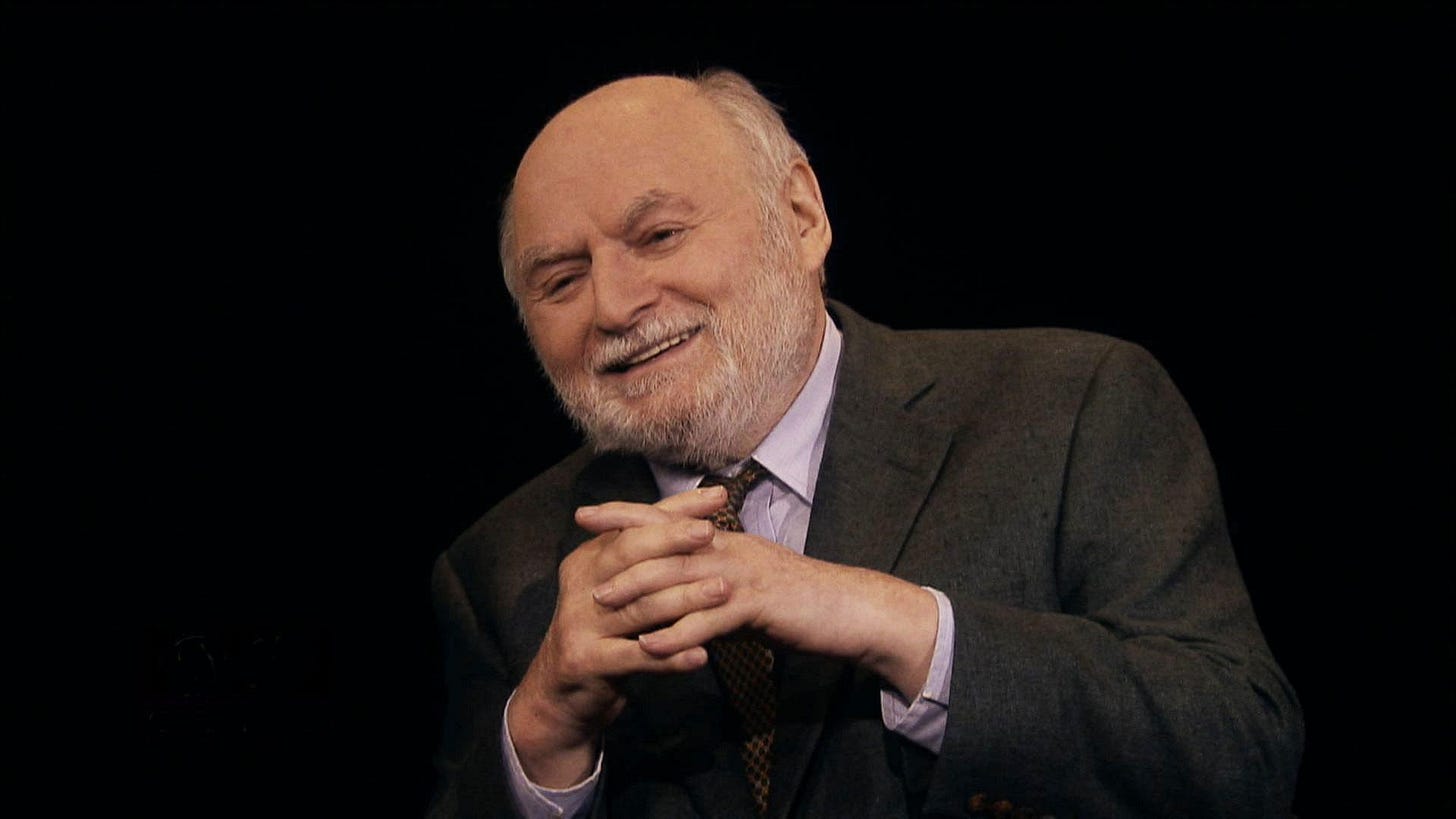

Victor Navasky was long venerated as an author, editor, publisher, wit, savant, teacher, mentor, friend, husband, father, and grandfather. At a melancholy shiva for him last winter, Max Frankel, the former executive editor of The New York Times, quoted his mother, Mary, a survivor of Nazism, observing on a comparable occasion, “They are shooting at my regiment.”

The little cluster around Frankel smiled and nodded in recognition.

Our regiment is a generation that came of age in journalism when we used typewriters to make deadlines for publications that came out daily, weekly, monthly, and were delivered on paper to homes, newsstands, and through the mail, with the benefit of time-honored cheaper postal rates.

The publications mainly depended on advertising and subscribers for financial support. The editorial and business sides were separate, “church and state” was the euphemism we used. Was it idyllic? No collection of people who call themselves journalists is ever satisfied – but the press was influential, a self-considered bedrock of democracy and free expression. This regiment was majority male. Those now in force are more balanced.

Victor died last January at ninety. And in August, Warren Hoge , another stalwart of the print age, died at eighty-two. While all of us born in the first half of the twentieth century are certifiably old, statistics from the Centers for Disease Control suggest that more than half of those born in the 1940s are still extant, and many continue to pound out words for what we call stories, articles, and pieces, wherever they now appear as posts, blogs, and links, measured for influence by the clicks they produce.

On a hot night in early September, Victor’s life was celebrated at St. Paul’s Chapel of Columbia University, where he had been a professor and chairman of the Columbia Journalism Review. Although the setting was a designated house of worship, the closest thing to religion in the memorial was the reverence we all had for Victor.

The eulogists were chosen from Victor’s colleagues at The Nation and Columbia, and from his family, which gave us the chance to revisit his warmth, wisdom, and humor. The event was not filmed, so I asked two of my friends to scan their prepared remarks to share and provide a sense of what was said.

Kai Bird, the biographer, was a former Nation assistant editor and Alexander Stille, a fellow professor at Columbia, had been a Nation intern – which seems to have been a bond that assured membership in the Navasky regiment.

To close the evening, Joan Baez came out of retirement to serenade Victor with “There But for Fortune.” The chapel was steamy and eyes all around were misty.

I encountered Victor over the years as a sometime part of his vast circle of social and professional contacts. We shared an especially close relationship to I. F. (Izzy) Stone, which gave me cachet enough in time to become the vice chairman to Victor for six years or so at the Columbia Journalism Review. My title was grander than my role. But I was able to watch close up as Victor went about his work as the Delacorte Professor of Magazine Journalism and honcho of the CJR.

His combination of savvy about the challenges of managing other people’s temperaments and the need to make financial ends meet when the magazine was, well, losing money, was a wonder. Every year, as budgets were being forecast, the possibility of closing the publication was considered. Somehow Victor contrived to find enough to hold the enterprise together. It was the humorist (and Victor’s close friend) Calvin Trillin who said that Victor was “wily and parsimonious” and paid authors “in the high two figures,” a capsule of his remarkable ability to get quality and a measure of acceptance for the payments he and his publications could afford.

Victor worked for a period at The New York Times as an editor, but his career was defined by his leadership of The Nation, where, against all historic odds, he made a profit and wrote books; among the best was Naming Names, the classic account of the McCarthy era in the 1950s, an ignominious moment in berserk American ideological anti-communism.

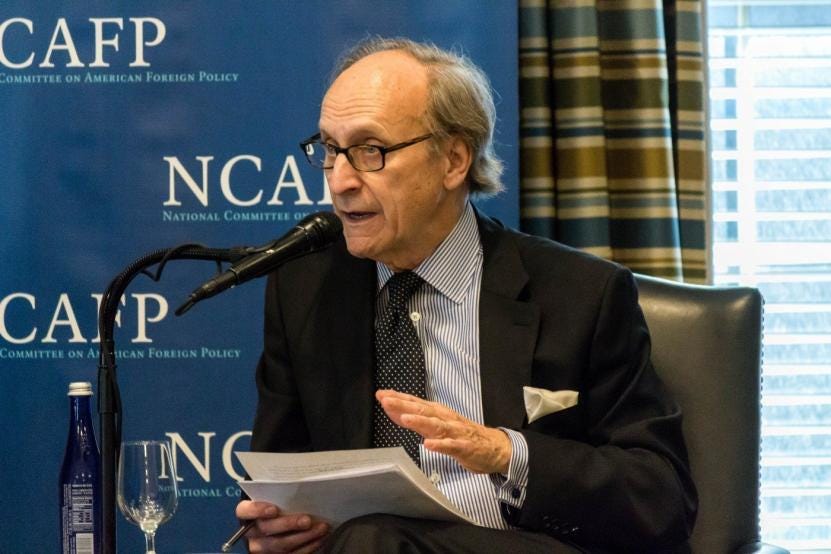

It was as a correspondent and editor for many years at the Times that Warren Hoge was widely recognized. His charm and stylish life working for the paper as bureau chief in Brazil and London and as a senior editor in New York had a different tone than Victor’s. And yet, to all and sundry, they were equally glamorous in their own way to the extent that the print generation in journalism at what are now called “legacy” institutions could be — set against the digital age of pervasive 24/7 inforrmation flow, increasingly on screens.

For us, the presses rolled. And we held the resulting papers and magazines in our hands. When there were bylines at the top of our stories, we could feel – but, of course, not always did – that we were doing something that would make, as the corniest of clichés goes, a difference in the world.

************************************

There is a new documentary called Radical Wolfe about the life and work of Tom Wolfe who died in 2018. The film also features Hunter S. Thompson with extensive commentary from Gay Talese and Michael Lewis, both of whom have new books being released in coming weeks. This regiment, then and now, is prone to performance and personality in their journalism which tends towards descriptions of realities that is of their own design.