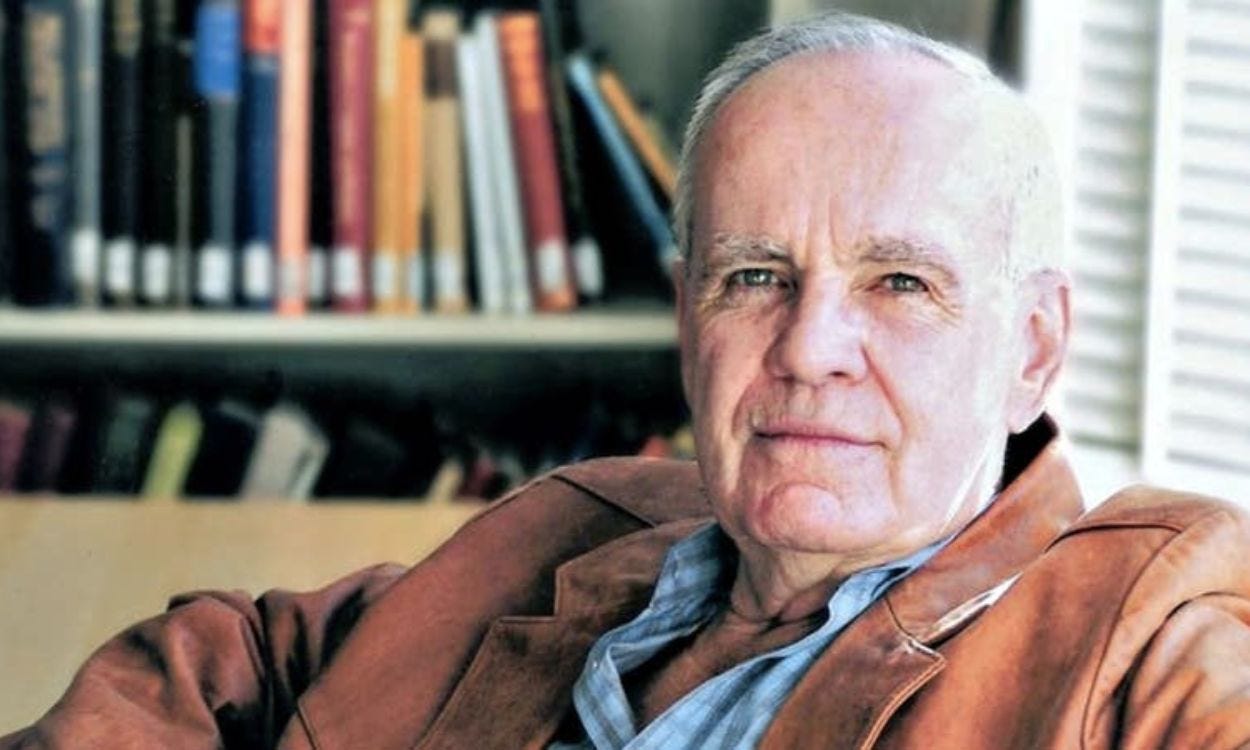

The death last week of the novelist Cormac McCarthy marked the passing of one of the most admired, even revered, writers in our era. The New York Times obituary summarized his life well. Two pieces I read over the weekend described the trajectory of McCarthy’s success in a way that reflects a side of publishing that is generally not examined or understood: Process.

Gary Fisketjon was McCarthy’s editor at Alfred A. Knopf, Dan Sinykin is an Assistant Professor at Emory University and author of the forthcoming Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature

Here briefly is what I know of that saga from a personal perspective, to make the point, again, that writers can benefit by knowing the system that brings authorial vision as close as possible to a desired outcome.

By April 1984, when I joined Random House as an editor, McCarthy had published four novels, all critically admired, none commercially noticeable. His editor was Albert Erskine, who had chosen to support McCarthy in the last stages of his own illustrious literary career. His list of authors, to be concise, was at the level of Nobel Laureate William Faulkner. Soon to retire, he was a remote presence (I never even saw him), and I was told that he now mainly oversaw James Michener, working with a full-time copy editor to manage the immense sagas that emerged from Michener’s typewriter.

Attending my first- ever sales meeting after a few weeks, another editor had been tasked to present McCarthy’s next novel, Blood Meridian, to the room. The editor’s speech pattern was hesitant and hard to follow. A few sentences in, Random House’s esteemed editorial director, the late Jason Epstein, whose leadership style was not empathetic, looked up and pronounced: “Cut the plot….” The announced first printing was 5,500 copies, the smallest on the Random House imprint’s list. In the catalogue, where most books got a full page, McCarthy merited a half page.

I remember the moment so vividly because arriving at this new job I was stunned, chagrined, and even a bit intimidated at the curt dismissal of an author’s work. What happened next is portrayed by Fisketjon and Sinykin in their recent pieces. In short, McCarthy, who had submitted his books to Erskine by himself in manuscripts with typing errors, cold-wrote to Lynn Nesbit, a superstar literary agent, who passed him along to a young, ambitious colleague, Amanda Urban, with already demonstrated keen instincts.

She wrested McCarthy from the Random House Trade Books imprint and sold his next book to Alfred A. Knopf, at the same company. There the publisher, Sonny Mehta,; the talented younger editor Gary Fisketjon,; and the marketing team led by the formidable Jane Friedman made All the Pretty Horses, published in1992 a major bestseller.

McCarthy, despite his sense of reserve, must have recognized that for all his talents as a writer he needed a process that would give him momentum in the marketplace. He said he had never ever before received a royalty check.

To be an author requires talent, stamina, and a capacity to endure frustration. There is great satisfaction in rendering words of consequence.

But publishing, ultimately, is a business – with all that entails. It involves a writer and the people entrusted with the work. To be successful, each part of that partnership has to respect the other – a bromide perhaps, which needs to be emphasized because it so often doesn’t happen.

As a nonfiction lit agent since 1989, I've explained a thousand - maybe a trillion - times to authors that publishing is, at the end of the day, a business, and thus they expect a profit. I think this has never been more true - or more difficult - than it is now. Most rush off in a huff and self-publish, assuming the genies or the fairies or something will magically lead people to find and buy their book amid the morass of +48 million other books on Amazon. Peter, as always, you hit the target with this beautiful and evocative post. Thank you for it.

Zombies don't read any books, much less good books. Trying to publish for money is a fools errand. Don't bother if you're in it for the money.